One book doesn’t happen all at once.

To make every individual copy from start to finish before moving on to the next one, a typeset printer would tell you, requires a stupidity generally reserved for goldfish and cable pundits (my phrasing).

One particular printer knows this better than most. Even though there’s a good deal of streamlining, rhythmic systems and expertise to their operation—they’ve been doing it for 51 years, after all—Larkspur Press only releases one or two titles a year, with a couple hundred copies each.

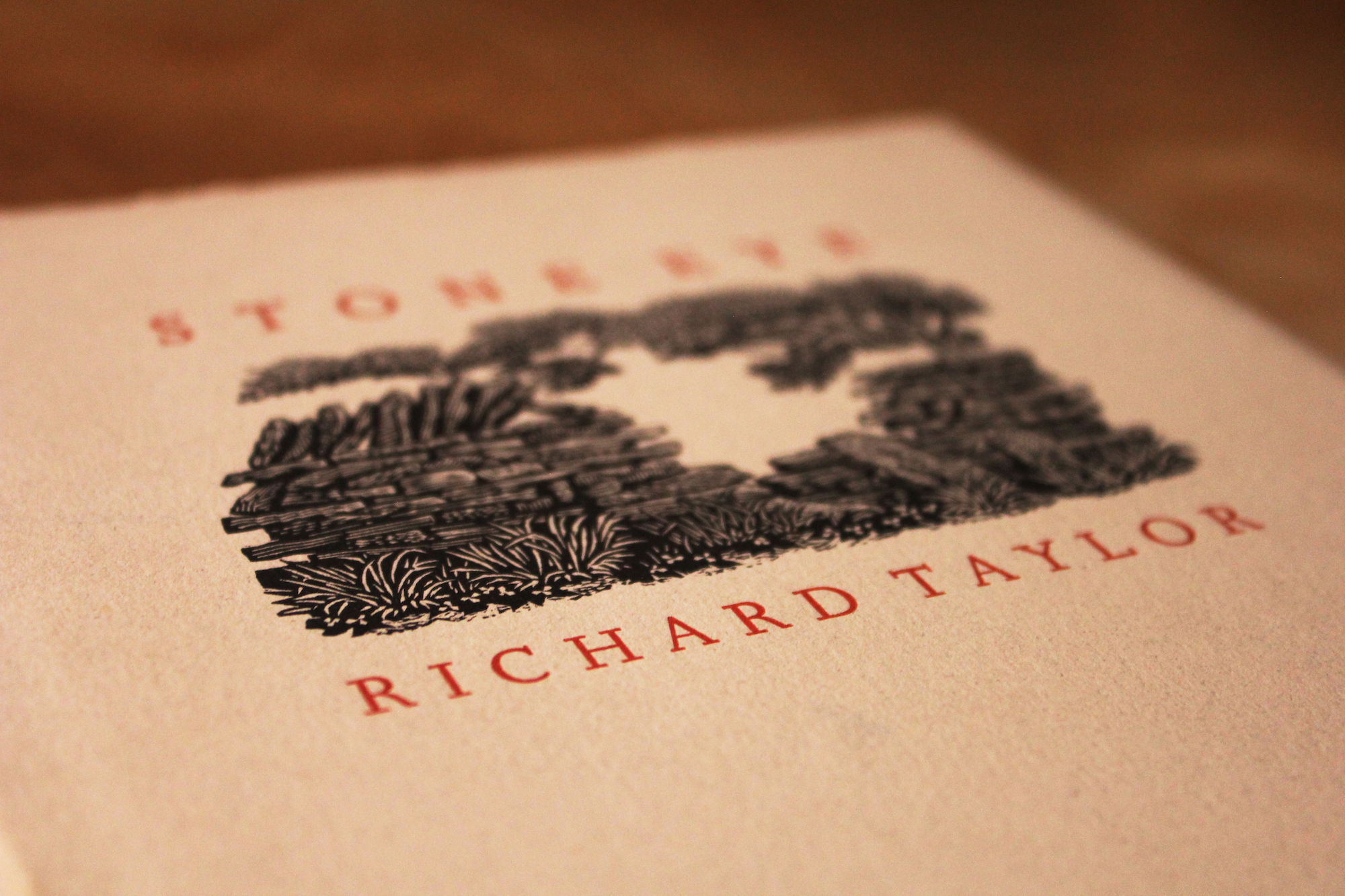

Larkspur’s owner and bookmaker-in-chief, Gray Zeitz, now in his seventies, admits that the number of titles the press makes per year has gone down as it’s aged. The quality hasn’t, though, and a Larkspur book’s cover layout is as unmistakable as ever.

If you happen to get ahold of any of these editions, it becomes clear that there’s something different about them.

There are the obvious features—the sunset red title on Richard Taylor’s “Stone Eye,” the Mark Twain–reminiscent woodblock-engraved cover of Wendell Berry’s “The Stackpole Legend” and so on—but those could come from any publisher. Larkspur books are remarkable for their idiosyncrasies.

The ink rounds every “r” differently. The words all but drag the eyes to the next line. The type, each letter set by hand on a 1916 (or 1915) Chandler & Price press, sits smooth and full apart from the paper’s rough tooth. There’s no such thing as a uniform font in a Larkspur book, and it’s that human element that drives Kentucky’s eminent poets to have Zeitz print their collections.

“Many of the poets he publishes are what I call nature poets,” said Richard Taylor, a former Kentucky poet laureate and a longtime friend of Zeitz’s. “There’s a natural connection there, and it has something to do with getting back to roots and away from all the artificialities of modern life.”

“It is important that we do not forget the elemental,” he said.

That has to go down, despite a noteworthy career, as one of Zeitz’s greatest successes. He doesn’t own a computer (“I don’t have time” for technology, he told me), and only a series of weekslong landline outages brought him to own a cell phone. He lives on a piece of land in Monterey, Kentucky (30 minutes north of Frankfort) near Sawdridge Creek and not much else.

His workshop and house are fairly close together, and to get to either, you have to cross a creek with a bridge that was seemingly built with the philosophy that guardrails are for cowards.

But, against what one may expect from that lifestyle, Zeitz is far from crotchety. At one point, he gestured at a picture hanging on his wall of a group of men sitting together on a bench.

“There was a grocery store there where people hung out,” he explained. “That was an everyday occurrence in Monterey, just right across the street from where I work.”

“There’s no place to (congregate) anymore for these guys,” he told me, pained.

He didn’t come off as cantankerous or resentful of modern society at all. He was just genuinely, kindly concerned about the direction his community was headed. (For the sake of journalistic completeness, he did curse about the new dollar store once or twice, but who’s immune from ornery vices?)

This connection matters to him: where most publishers will take an edited manuscript and work silent magic with it, Zeitz is in constant communication with writers as he’s making their texts come to his own version of life.

His day-to-day isn’t quite as regimented as it used to be, but he still works fairly standard hours and is content to spend an entire day doing the same task over and over again. A book enters Zeitz’s workshop and, though it may take an election cycle or two, every step of the bookmaking process is done in his one-and-a-half floors of space.

“When a manuscript comes in here and I decide that I want to do it,” Zeitz said, “I will usually do a design for it.” He composes a blank page based on Fibonnaci’s Golden Ratio and lays out the page based on it as a way of satisfying the eye’s natural instinct of where to go next. This is in contrast, as Zeitz pointed out with a twinge of earned righteousness, to poetry collections whose publishers align the type of every poem on the left, futz around with spacing and break for lunch.

Then begins the typesetting. Zeitz has chests with each hand-labeled drawer dedicated to a font and size—“Garamond 14pt.,” for instance—and he lays out each letter by hand, feeds paper into his press, and uses a lever to apply ink to the page. He runs five pages of poetry in the press before pulling the lever once with no paper in as a way of resetting the mechanisms.

“I’ve got a system down,” Zeitz said. “Just a little dance.”

That dance has treated him kindly. He paid off any debt a long time ago, and though he continues to charge enough to live comfortably, his books don’t cost as much as they could, especially for special editions. (Boasting marble covers and mould made paper, Zeitz routinely charges in the $200 range for these. It’s a big number, indisputably, but it’s peanuts compared to the $1000 figures that other letterpress printers toss around for books of that quality.)

In fact, with paperbacks that sell for $16-20, one would be hard-pressed (pun intended) to find a mass-produced book that costs less. Zeitz makes a living doing this, and he supports a small group of employees in the process, but there’s more to why Zeitz, an accomplished poet in his own right, has devoted his professional life to this endeavor.

For every book Zeitz prints, that beautiful setting usually comes in three forms.

The first is the hardback, or “regular.” Like everything else, Larkspur does the binding and the cover paper proves remarkably durable. These may run for $30.

The paperbacks are sewn by hand in house on the same machine-made paper from the Mohawk Mill in New York as the hardbacks, and usually cost $10 or $12 less.

“Then we play.” Larkspur’s aforementioned special editions are rare—usually only a few will accompany a new release. This is in part because of the triple-digit price tags, but it’s equally a result of the exhaustive labor that goes into every individual copy.

They’re usually the only editions Larkspur will make with mould-made, as opposed to machine- or hand-made, paper.

Making paper with a mould involves a rotating cylinder in a vat of paper stock. When the stock touches the mesh on the cylinder, it forms a web, which is then sent down a conveyor belt and into a machine that presses it into paper.

Special editions also have marbled colors, a process by which pigments (which can either be bought or taken from boiled moss) are put onto paper to form a design. They’re set by a solution and left to dry for a while, but beyond that, marbling is labor-intensive and subject to human flairs—no two covers are exactly alike.

The occasional book will have a fourth edition. These are leather-bound, often by Gabrielle Fox of Cincinnati, and they routinely fetch sums that would make Karl Marx cry himself to sleep. In one case, a Fox-bound Larkspur edition of “Sabbaths 2002” by Wendell Berry sold to a Scottish buyer for $1600—in a specially designed wooden box, of course.

With such a robust reputation, Zeitz had every right to tell me, “I don’t mess up too many sheets.” But he also readily admits that any good printer is always studying. There are a few other operations like his that he can learn from and whose owners he can call friends.

Deborah Kessler runs one of these, October Press. Kessler works with Zeitz extensively, and studied his particular methods at Larkspur for years.

“It [was] an oasis for me,” Kessler said. Zeitz gave her a Chandler & Price press once she had space of her own, but in the meantime, Kessler drove from Lexington to Monterey (an hour both ways) to work with Zeitz on weekends and whenever she had time away from her job—fittingly—as a librarian.

The two have worked together in one way or another for 25 years, a match made by Richard Taylor, a bookstore owner himself.

Though all of Zeitz’s employees—past and present—do all sorts of work, Leslie Shane does most of Larkspur’s binding, which includes hand-sewing paperback covers. But Larkspur is jack-of-all-trades in nature, and though Shane has this specialty, she has done every step of the bookmaking process countless times over—and learned it all from Zeitz.

Shane moved to Monterey after college but taught Montessori school for 30 years before she became a printer. She met Zeitz in college, and around 1970, he invited her to a Christmas party at his shop, which was the first time she’d ever seen a press like his.

About a decade later, community members began to put on arts and crafts workshops in the summer, and Shane grew to appreciate Zeitz’s work. She shortly began dividing her time between an apprenticeship at Larkspur and her Montessori job before switching to the former full-time.

Even with Kessler and Shane, there are days when Zeitz is the only one in the shop, and with those days in mind, it’d be tempting for someone who hasn’t visited Larkspur to think that much of Zeitz’s work is done alone. I did. It isn’t.

The printing shop is chocked full of old Larkspur editions, some from writers I’d never heard of, others from ones I shook at the prospect of contacting for comment. He showed me books worth more than my kidneys, one of which was a text that had been translated to English but had Chinese script done by a calligrapher that the translator happened to meet in a Bowling Green restaurant.

Zeitz has become part of a tradition that’s existed since Gutenberg, and though Larkspur makes most editions from start to finish, every name on every cover or copyright page is proof that he doesn’t work alone. Taylor may be right that Zeitz has escaped modernity’s vices but, more than most people can dream of, he’s embraced its connections.