REVIEW: Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings provides insight to Asian-American culture

Shang-Chi is relatable to Asian-American viewers and also entertaining enough to retain Marvel’s general audience.

September 5, 2021

You sit down in the movie theatre to watch another Marvel movie. After the ads finish playing, you hear fluent Chinese and see subtitles on the screen. Soft traditional Chinese music plays in the background of a Kung Fu fight that has more of a graceful touch to it as the camera slows down on each of the characters’ movements.

“Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” is very different from the typical Marvel movie. It’s not particularly spectacular in terms of special effects as compared to other Marvel movies, but it stands out in its relatability to East Asian audiences. Not only through its actors and soundtrack producers mostly being ethnically East Asian people, but its showcase of both ancient and modern Chinese culture adds unique representzation that isn’t rooted in stereotypes nor whitewashes the characters.

The movie, directed by Destin Daniel Cretton, creates a dichotomy between the karaoke-loving, laid-back Chinese-American culture with traditional Chinese culture that involves dragon motifs and martial arts. Immediately after the starting fight between Shang-Chi’s father Wenwu, played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shang-Chi’s mother Jiang, played by Michelle Yeoh, the movie cuts straight to the two main characters joking around in English as they speed in a sports car as valets in America.

Most of the movie centers around Shang-Chi, his best friend Kat and his sister Xialing. Shang-Chi displays the sharp contrast between Chinese-Americans and mainland Chinese people through its characters’ distinctions. Katy, played by Awkwafina, is shown to be only loosely connected to her Chinese roots. When she first encounters Wenwu, the movie puts a large emphasis on the fact that she can barely pronounce her Chinese name while the father comments on the importance of a name and its connection to one’s ancestry.

Compared to Xialing, played by Meng’er Zhang, whose entire career is based on her martial arts skills, Katy doesn’t know much about her culture despite being raised by a fully Chinese family. Shang-Chi blends these two archetypes as someone who was raised in different aspects of Chinese culture by his parents, but then was also partially raised in America when he ran away from his father as a 14-year-old.

Shang-Chi definitely makes an effort to explore almost every aspect of the Asian experience. As part of introducing Katy, she and Shang-Chi, or “Shaun” at this point in the movie, lightly mention the racism he experienced when he first came to America. The movie even goes into the more niche experiences of being Asian, as seen when Katy’s family asks Shang-Chi when he’s going to propose to Katy, but then he tells them they’re really just friends. The assumed nonexistence of male-female friendships exists in western culture, but I think Asian families especially have a bit of an obsession with wanting their children to marry as soon as possible because of the importance Asian cultures put on ancestry and family.

While Cretton may have intended to make their relationship platonic for reasons relating to Shang-Chi’s inner struggles, their friendship also helps to go against the outdated expectations of Asian families to nudge their children to marry any opposite-sex person they’re close to.

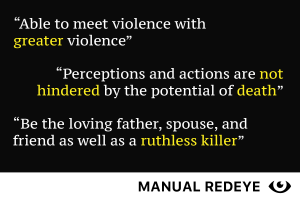

The movie also does well in its exploration of the Chinese patriarchy. Shang-Chi’s father was a violent man who traumatized his children all in the name of revenge for his dead wife, but in the end the movie still shows that he did love his children when he sacrifices his life to save Shang-Chi. Ignoring the fact that his father died from getting soul-sucked by a CGI dragon, the scene was touching in a way.

A joke among Asian-Americans is that all of us have the memory of our immigrant dad yelling at us for hours for getting one math problem wrong. Obviously, Shang-Chi’s case is a much more exaggerated version of the kind of tough love that’s common in Asian culture where sacrifice is held highly, but it still makes the movie especially relatable to Asian-American children whose parents left everything for their current lifestyle.

While it’s nice that the producers literally made a list of Asian stereotypes to avoid when designing each character, so audiences don’t emasculate Shang-Chi or fetishize the female characters, I feel like they overdid it at times. Marvel movies in general have a problem with relying on the main character’s best friend to act as comedic relief even in the serious moments, and it repeats in Shang-Chi.

For the first half of the movie, it seemed like the producers really wanted Katy to fit the sarcastic, cool girl trope to counteract the soft Asian girl stereotype, but a lot of her dialogue with Shang-Chi sounded so unnatural sometimes, it came out as more cringe-worthy than funny. This did get better in the second half as Katy matured from getting in touch with her Chinese roots, but her character still could’ve been just as sarcastic in the beginning without being overdone.

Overall, I thought “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” was a perfect mix of being visually entertaining to general audiences while also providing unique insights to Chinese relational culture that the smaller Asian-American audience can especially appreciate. Before the end credit scenes that hint to the next Marvel movie, the movie fittingly ends on the one activity that connects both mainland Asians and Asian-Americans, and that’s singing Hotel California in a karaoke bar.