BHM: Weaving of Black artists in Noel Anderson’s work

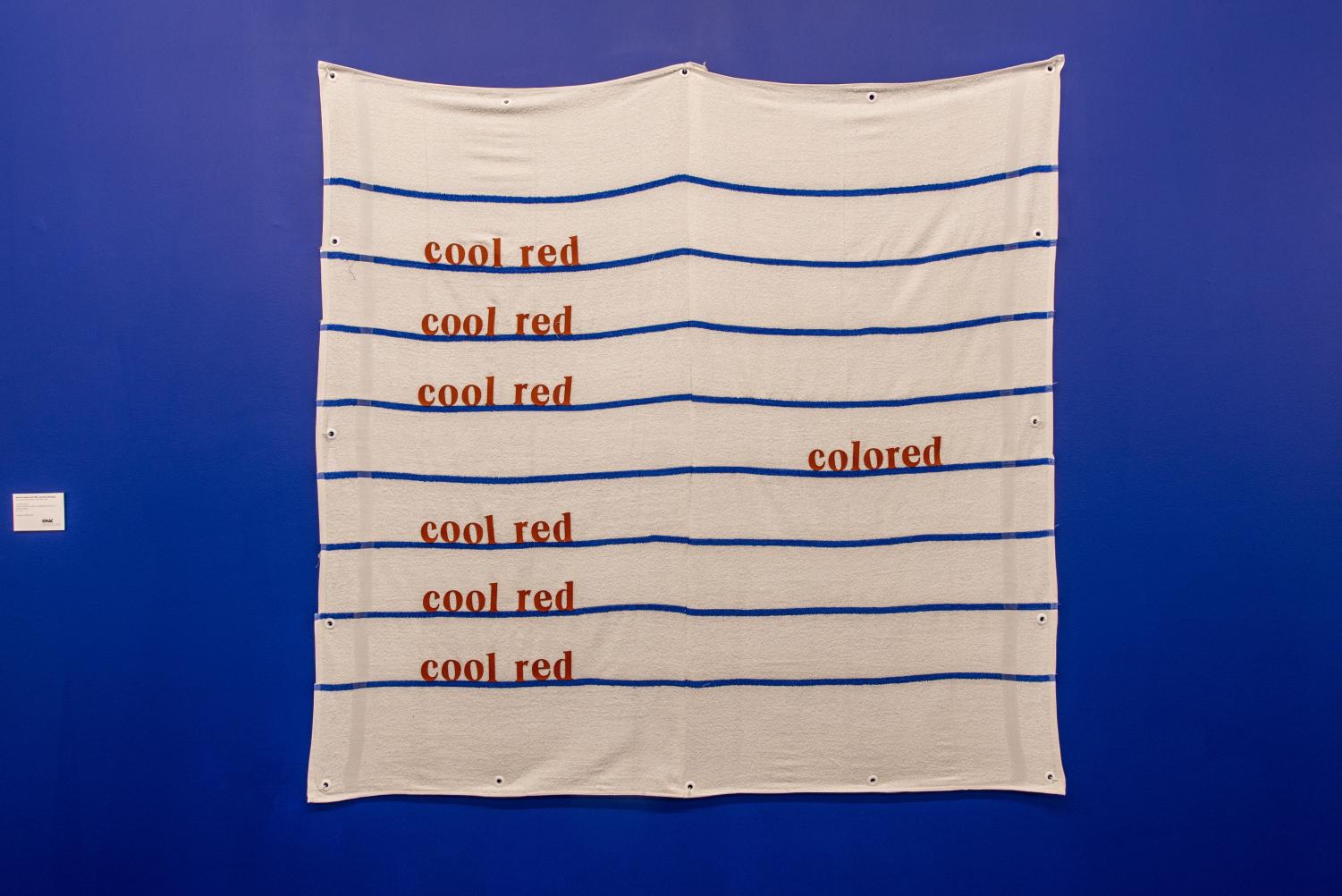

One of three pieces made from athletic towels in the exhibition, “Cool Red” encourages Black viewers to define themselves with words and erase the hateful words placed onto them.

February 28, 2023

Quan wrote this profile in collaboration with Arts Angle Vantage, a youth arts journalism program Quan has been involved with since 2022.

On a January school day, two groups of West End School fourth graders entered their art room jumping around but slowed to give their shoes a break and gather around the table with an art professor to discuss the most pressing topics: peanut M&Ms, African identity, New York City rats, artistic potential, LeBron James. Their value.

Louisville-born artist and professor Noel Anderson was on a hometown visit from his art studio in the Bronx, New York, for his exhibition at KMAC Museum titled “Erasure’s Edge” (The show ran from November through January.) Anderson makes it his mission to find schools wherever his art shows are to do projects with students.

At The West End School, Anderson fielded students’ opinions about their preferred candy, their favorite sports and athletes and their takes on art.

The visit was a perfect opportunity for glitter and glue loving fourth graders to make some arts and crafts. But Anderson diverted from the glitter and glue during his visit as he simply pulled out his chair to talk and listen.

“That distraction takes away from the strategies that we could really build at this table by talking to each other,” Anderson said in a later interview.

Talking to young students has cultivated Anderson’s teaching abilities into something more than he had imagined. It’s one thing to teach college students, he said, but it’s another to get fourth graders to think about their own capabilities.

Noel W. Anderson, currently the Area Head of Printmaking in New York University’s Steinhardt Department of Art and Art Professions, was born in Louisville in 1981. Today, much of his art practice specializes in weaving and tapestries. While his work frequently takes him to France and various parts of the United States, he always returns to his hometown.

This is where he first began his creative journey after all. While a student at Ballard High School, Anderson played basketball and football, believing sports were his only pathway. Although he continues to love physical activity, he began exploring his artistic abilities after taking art classes in high school.

With the West End School students, Anderson talked about the elements of art and their mutual love of basketball.

The literature accompanying “Erasure’s Edge” covers the rise of Black athletes in basketball and how it played a transformative role in not only the entertaining aspect of viewing basketball but also in opening up the doorway for Black people as entertainers in popular media.

Basketball is one of the only fields of Western media in which Black people are free to dominate, he said. Anderson sees basketball as a modern extension of superhuman expectations that white crowds have ascribed onto Black people, drawing back to a source of the 19th and 20th century public lynchings of African Americans. Then, there were accounts of white people shooting multiple bullets in dead bodies out of fear that Black people somehow have a superhuman ability to revive themselves and attack in vengeance.

Although televised basketball may have had a positive influence on Black people’s position in the media, Anderson believes sports often overshadows the potential for Black youth to excel in other fields like art.

Anderson expresses this idea through his basketball-themed pieces, many of which were in his recent exhibition at the KMAC Museum. Anderson chose the show’s title “Erasure’s Edge” and the works to counter the “act or instance of erasing” (“Merriam-Webster’s” definition of erasure) of Black men in media. He plays with this definition through physical methods — bleaching and rearranging Black representations in media in order to remove the negative, violent depictions of Black men and make room for better, more accurate representation.

“I take that mob, which at one time was killing us,” Anderson said. “And now it’s cheering for us, but still killing us.”

In his piece “Cool Red,” a bright blue wall is a backdrop to an oversized athletic towel that replicates a page from a notebook. Line-by-line the words read, “cool red, cool red, cool red.” Then, the viewer’s eyes see on the right side, the word “colored” sandwiched between the repeated lines of “cool red” above and below. It’s disorienting and seemingly innocent. That innocence is then broken up by the very word used to separate people during the Jim Crow Era.

Each letter is also individually cut from the exterior leather cover of basketballs. Anderson finds that the material used to make basketballs have a resemblance to Black skin.

Just as Anderson forms and reforms words using letters made from basketballs, he wishes more Black people would look more closely at how to use words to define themselves.

In his own youth, Anderson believed that his only path was sports. His father introduced Anderson to jazz, which first sparked his creativity. Then in high school he fell in love with biopics about artists like Michelangelo as depicted in the 1965 film “The Agony and the Ecstasy.” It inspired him to explore his artistic passions. His parents supported his passion by buying art tools and manuals. He’s grateful his parents’ found value in his pursuit of art, which is often rare in families of color due to the field’s notoriety for low wages.

Feeling like the only path is sports is not unique for Black youth. He wants to ensure that, despite this, today’s youth have a strong support network.

Reflecting on The West End School students, Anderson said he finds pride in this generation of Black youth who are still finding themselves.

“They just have so much possibility,” Anderson said.

It’s this blank canvas that makes it so critical to teach Black youth about their potential and stepping away from stereotypes.

Meeting with students like these at The West End School is akin to passing a torch — one he feels that he got from his parents and their generation. Before him, he saw a support network of Louisville Black artists that provided for each other.

Among them is Sam Gilliam, a Louisville-raised artist who greatly inspired Anderson’s work. Internationally recognized, Gilliam, who graduated from University of Louisville and died at 88 last year, is most famous for his abstract “drape paintings” that revolutionized the dimensions of art itself.

Along with an artistic connection of their philosophical approach to tapestries, Anderson also has a familial connection with Gilliam, as his own grandmother helped to raise Gilliam. Then in 2021, Anderson’s work was on view alongside Gilliam’s in an exhibition at the Speed Art Museum “Promise, Witness, Remembrance,” which commemorated Breonna Taylor. The show also included works by several others in Louisville’s community of Black artists like Ed Hamilton and William M. Duffy.

It’s a big change from what Anderson saw when he was growing up.

“At the Speed Museum, I never saw images of me… us,” Anderson said.

But now as an established artist and talking to the West End School classes, Anderson stood in front of Ms. Ashley Screetch, the art teacher, where she presented him with the students’ self-portraits. In their works, they define themselves in their own words.

“I would be honored if I could put your work in the show with me, so I could tell Louisville that I’m not the only one,” Anderson said.

KMAC saved a wall at the exhibition for the students’ self-portraits to showcase alongside Anderson’s works.

As Anderson conveys his ideas of erasure, he’s acting as a bridge between generations. He passes on the inspiration he’s received from older generations of Black artists and weaves that together with a passion to inspire future generations of Black youth in Louisville.

“For everybody at this table, we have value,” Anderson told the students. ”And one way to show you have value is to make art.”