“Of all the unimportant things, football is the most important.”

That aphorism is often credited to Pope John Paul II, but to leave it there as a launchpad into the article would sacrifice some nuance. For one, John Paul probably wasn’t the one who said this—and, even if he were, he wasn’t talking about American football. Still, the fact that the saying is attributed to him to begin with—and that it’s become so popular—says something.

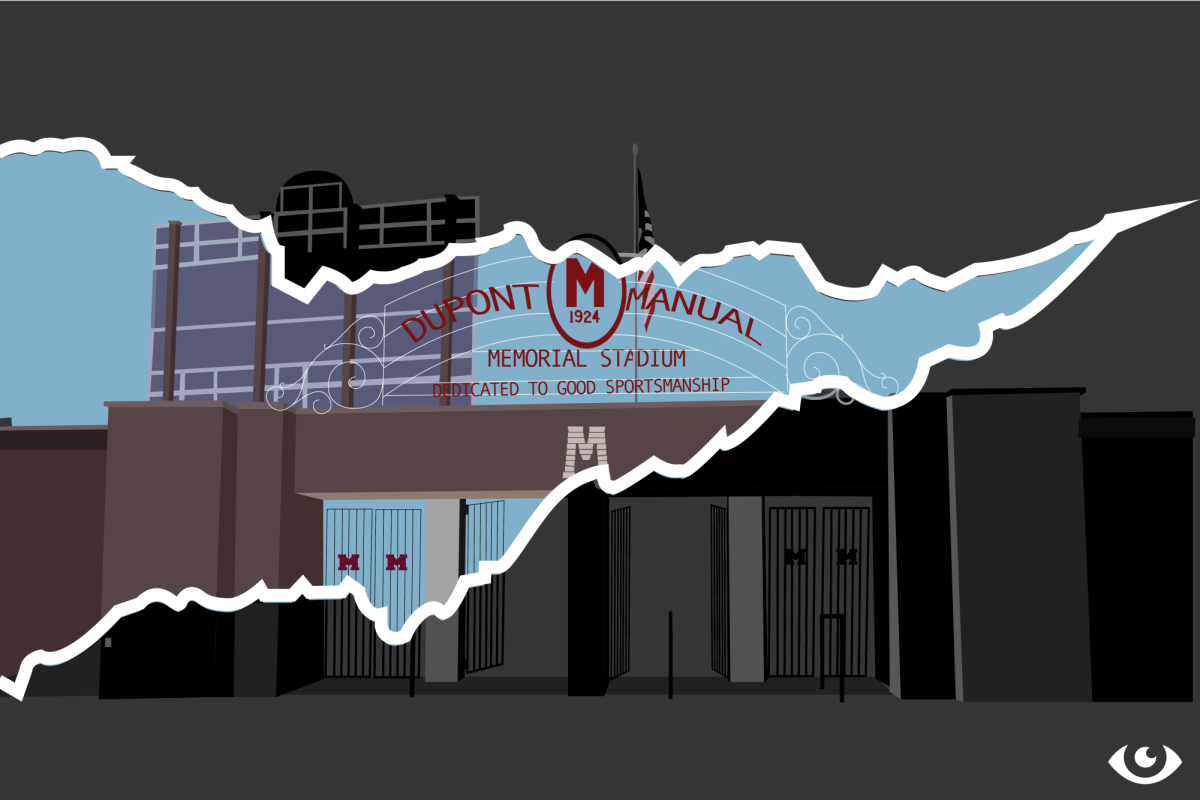

It’s impossible not to confront at least once the fact that, in the scheme of things, sporting events don’t capital-M Matter. But humans are constantly, notoriously, beautifully hungry for things that bring them together, and there’s an almost religious feeling—the quote is attributed to a pope, after all—that comes with supporting a team that you and generations before you have built. It was this feeling that drove Manual community members a century ago to build the now-historic gate in front of Manual stadium in just one day.

The Crimson football team played the stadium’s dedication game on November 15, 1924, against Washington High School of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Manual lost 6–0, and never seemed to make much of an effort to score, but it didn’t matter.

“[Manual athletes], homeless since the birth of their first brother, came into their own with the dedication of the duPont Manual Stadium,” the Courier Journal’s loquacious Bryce Dudley wrote at the time. “Here at last was Home, Home after 30 years of wandering and wondering.” He went on to describe the team’s journey as “waifs at the mercy of landlords.”

Whether he was verbosely chronicling a monumental moment for an underdog or trying to fill column space after an unspeakably dull loss, history will never know.

But that is, to an extent, the story of the stadium that recently celebrated its 100th birthday. Its home team has lost more than a few of the games played there, but in a century of matches, the crowds never dwindled.

“It’s just full of memories,” said Manual football alumnus and president of Manual’s Alumni Association Wes Jackson. “The first thing to understand is just how long 100 years is.”

And he isn’t wrong. It’s easy—and fair—to say that the world Manual Stadium entered was less connected and less tolerant than ours. The Courier Journal covered its games in exhaustive depth, but not before featuring a section devoted to news for women (largely comprised of ads for clothing stores). The era also saw rampant racial inequity, and all society’s woes were broadcast on an arcane, brand new, supposedly corrupting technology: the radio.

It’s also easy to ignore this and focus on the game. And there’s plenty to focus on, from Manual’s 81–0 loss to Louisville Male in 1919 to a 1948 match that became so crowded that the announcer had to climb atop the press box to narrate.

But this, too, is incomplete. Schools and communities can’t be divided so neatly. In 1968, for instance, they collided when a mass student protest followed the appointment of a white quarterback over a more talented Black one. The lesson that the stadium has kept teaching, from the first match described oh so wordily, is that nothing serious or groundbreaking has ever happened in a vacuum.

Even the stadium’s birthday, an event largely consequential only to Manual itself, was made all the more significant when the Metro government awarded it historic landmark status.

“[The announcement] is an opportunity to recognize the amount of historic contribution duPont Manual has had on our community,” Principal Dr. Michael Newman said.

It’s a storied institution, to be sure—but, as Athletic Director David Zuberer put it, “it’s clear that it’s 100 years old.”

That’s obvious when you pause a moment and look at it, but in the sasquatch thunder of a game, if anyone recognizes that history is being made simply by clocks ticking on the stadium walls, they don’t say it. There’s more pressing things to talk—or, more precisely, scream—about.

When he started playing, “all I really knew was that the stadium was really old,” football player Cash Zuberer (#18, 12) said.

There are, after all, different things in the team’s focus—including, as Zuberer reminisces, running up the hill at the end of the endzone after every victory.

“The atmosphere here, especially when we have a big game, is crazy,” Aiden Blakey (#8, 12) said.

Manual Stadium has had that atmosphere since its construction, and its past builds on itself, but 100 years of weekly explosive energy has proven to be an exhausting feat of endurance for the arena. The evidence of this feat—from old bleachers to worn-out grass—isn’t hard to come by. In 2023, JCPS announced renovations to athletic facilities, including a host of changes to Manual Stadium, most notably a switch from real grass to astroturf.

The change, though the Manual administration argues it’s necessary, is unquestionably bittersweet. There was even some ambivalence on the team about whether the change is a good idea at all.

“I would rather Manual stay grass,” C. Zuberer said. “It’s still a memorable place, but it’s not the same field that everybody else has played on.”

Even so, with countless teams using the field year-round, the change is happening anyway, and players are making the most of the grass’s last year.

“It was always fun playing at the field, and to know that we’re the last team that’s going to play on that field [was a special experience],” Blakey said.

And that century of history that’s scuffed the stadium’s walls itself didn’t pop out of nowhere. It came into existence after decades of 19th century bureaucracy ended with two Louisville high schools, Male and Manual, competing with one another after one was built in the other’s literal backyard. Manual moved, merged back with Male, and the two were ultimately re-split with the rivalry in even fuller force—a driving reason for the stadium’s construction in the first place.

All that should’ve toned down the mutual resentment, but it only made it burn brighter. The Male-Manual competition is, at its core, a sibling rivalry.

That reveals the truth, sandwiched between player anecdotes and bigoted societies, of why Manual Stadium has endured so long despite its modest (again, 81–0) history. It may not make sense to care so deeply about running up a hill or commemorating a decrepit stadium, but humans are going to seek unironic passion no matter what, and it’s easier when it comes with something to be against.

There’s a paradox nestled somewhere in the fact that we use sports to artificially divide ourselves in the name of feeling more united. But as nostalgia wears away the anger of defeat and sweetens the joy of victory, the stadium holds fast, and its community lives with it. And that’s certainly worth commemorating.