Conventional wisdom might suggest less intense stress reduction. These recommendations are the stuff of pamphlets—bubble baths, meditations, milquetoast background piano music and so on. Those can be great (I’m not here to judge anyone), but they all share a central flaw: they turn off your brain, rather than centering or strengthening it.

These albums, in ascending order of experimental madness, are arranged with a different approach in mind, one that jazz may well have been designed for. They won’t just dull anxiety; they’ll exorcise it.

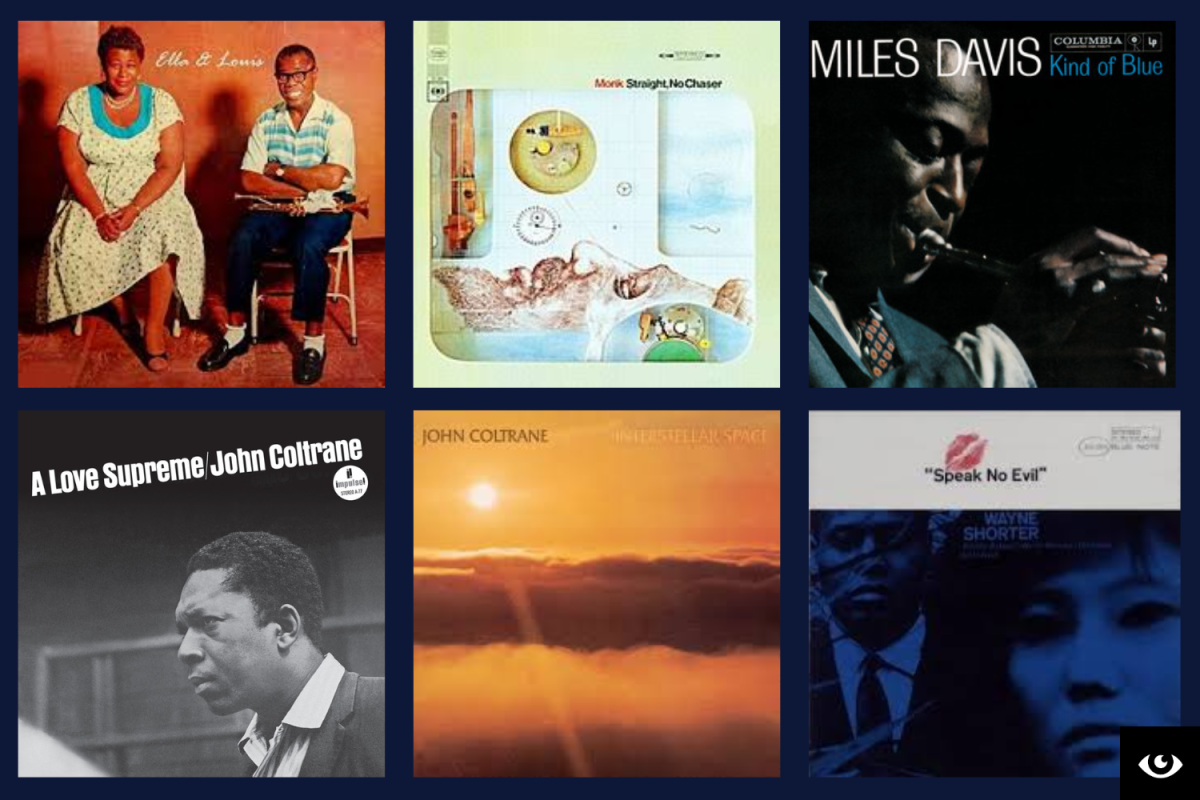

“Ella & Louis” by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong (1956)

Some jazz snobs reflexively look down on lyrically-driven pieces. They’re right that it limits the potential for improvisation and, no, it doesn’t lend itself to pure, in-your-face shows of instrumental talent, but the accusation that it isn’t as sophisticated as lyricless jazz has no better rejoinder than this classic album.

It’s a masterclass in making the listener wait. When Ella Fitzgerald is singing her part in a duet, you miss Louis Armstrong; when Armstrong is singing, you miss Fitzgerald; and if they’re harmonizing, you miss Armstrong’s humming trumpet. The balance is delicate, but with the record’s exquisite musicianship (especially the reserved genius of legendary drummer Buddy Rich) and effortlessly soul-hitting vocals, it’s perfect.

“Straight, No Chaser” by Thelonious Monk (1967)

Enter the instrumentals.

At first glance, this album—with its mid-tempo swing and tendency to stay in one key—could reasonably be called “coffee house jazz.” But, just as “Ella & Louis” is more than simple duets, “Straight, No Chaser” is more than simple bebop.

There are two tracks in particular that exemplify this: “Locomotive” and “Japanese Folk Song.” “Locomotive”’s name more or less admits what the track is trying to do. It has all the usual swing and finger-tap-ability of radio-friendly jazz, but every time it seems to settle into repetition, Monk’s piano playing propels the rhythm forward like coal in the engine room.

“Japanese Folk Song” is even less of a generic jazz piece. After a stellar piano solo, the track—itching with restlessness—launches into full swing. Every time you think it’s becoming predictable, you’re hit with a drum fill or an off-key piano chord. Monk is showing you that you ordered his music, straight, no chaser, and that he’d sooner die than water it down.

“Kind of Blue” by Miles Davis (1959)

I’ll be the first to admit that, of all the records on this list, “Kind of Blue” sounds the least exceptional to a contemporary listener. But, just as one might tell a student who doesn’t get the cultural love of Shakespeare, it’s important to realize that the only reason Davis falls within the norm is that he set it. Besides, whether or not it’s groundbreaking in 2025, the album is as moving as it is enjoyable.

The best display of what the album has to offer is “Blue in Green.” While it sends up with the same mid-tempo, walking bassline and casual improvisation of the other songs, its beginning—with piano tremolo and behind-the-beat drumming—point to a visionary quality that makes Davis’ masterpiece well worth a listen.

“Speak No Evil” by Wayne Shorter (1966)

Shorter isn’t as much of a jazz titan as the other artists on this list. But I didn’t promise an introductory course (something I’m in no way qualified to do), I’m offering some excellent jazz albums, and it’s on this promise that Shorter delivers.

Not only did he take classical impressionism (the stuff of early 20th century composers like Claude Debussy) and translate its unexpectedness and hazy emotion into improvisation, he managed to arrange pieces with the care of a surgeon to pioneer a style of harmony that makes “Bohemian Rhapsody” look like “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

There’s plenty that could be said about the album as a whole. The title piece has a catchy trumpet motif and a drum beat that balances outward energy and collapsing rhythms with the forceful technique of a red giant star. Still, “Speak No Evil”’s most sophisticated showcase comes one track later: “Infant Eyes.”

Jazz is a genre known for subverting norms, but even with this expectation, any layman or scholar hears “Infant Eyes” and knows they’re in the presence of something new.

Not only do the chords dance around keys (musical and piano) within the first four seconds, the recording’s crackly undertone and lax tempo provide a perfect nook for every instrument to improvise—in or out of time and key—without the listener feeling attacked. Shorter not only manages to convince you that his music is breathing, but that you’re breathing with it.

“A Love Supreme” by John Coltrane (1965)

“A Love Supreme,” Coltrane’s masterpiece and a candidate (alongside “Kind of Blue”) for the greatest jazz album of all time, was recorded in a creative burst that followed his religious awakening and subsequent abandonment of his drug habits.

The album’s liner notes say it all. “At [the time of my awakening], in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music. I feel this has been granted through his grace. ALL PRAISE TO GOD.”

The notes end with a similarly zealous poem that shares the album’s name.

“A Love Supreme” comes in four movements, each featuring saxophone, drums, piano and upright bass. The talent of the ground is impeccable; even when a note is “wrong” by any possible music theory definition, it fits perfectly in place. The tempo is never a beat too fast or too slow. There are repeated melodic flourishes performed with the pious discipline of prayer, surrounded by improvisatory explosions played with the blissful lightning of revelation.

The first movement ends on a note of uncertainty that the rest of the album doesn’t resolve. In the record’s only lyrics, at the end of the movement, Coltrane sings “a love supreme” with the same melody as a motif that various instruments had repeated at different times throughout. But there are two vocal tracks overlaid, and they’re dissonant—one voice is slightly lower than the other. Coltrane is saying that, in spite of everything, his journey isn’t finished yet.

“Interstellar Space” by John Coltrane (1974)

“Interstellar Space,” the last Coltrane album recorded before his death, very much feels like the furious and all-in resolution to whatever he started in “A Love Supreme.” In “Supreme,” the music is some sort of prayer or appeal. This album—with only Coltrane on the saxophone and Rashied Ali on the drums—is hellbent on summoning God himself.

Forget everything you know about keys. Forget everything you know about time signatures. Coltrane and Ali’s only restrictions are the very limits of their physiologies—and some of the drum solos seem to challenge even that. The album’s four tracks (except for “Saturn”) are bookended with Coltrane ringing jingle bells for about ten seconds, as if to call the communion of saints to order, before the music goes wherever it chooses to go.

The fact that it was recorded with only a vague idea of its shape laid out confirms what many listeners know intuitively: these pieces aren’t being performed so much as revealed, and the playing is so virtuosic that one feels like they’re witnessing something they aren’t supposed to hear.

I promised stress reduction, and this album provides that. Where “Ella & Louis” is a nice cup of tea, “Interstellar Space” is electroshock therapy.

Z • Feb 14, 2025 at 8:05 am

I love Thelonius Monk omg!