Black History Month is a time to remember black individuals who have shaped the world but who’s stories remain untold, or even erased, and none more so than the people of the LGBT+ community. These are a few of history’s most iconic queer people.

Ma Rainey, the ‘Mother of Blues’, was so openly gay in her music and life that in 1925, police arrested her for allegedly throwing lesbian orgies. After raiding her house during one such event, police found that all of the fleeing party-goers were women. A close friend, bisexual blues singer Bessie Smith, bailed Rainey out of jail, and police dropped all charges due to the only evidence of the crime being the fact that all the attendees had been in various states of undress. Rainey was a unique, uncut voice singing about real—and often risqué—topics in an era that remembered slavery all too clearly. She sang about the degrading menial labor many working class men and women had to shoulder in order to feed themselves. She also discussed topics such as abuse and violent relationships as she sang with raw emotion that displayed the inequality, racism and daily fight of existence that came with living as a black person in America in the 1920s. According to the book Queer, There, and Everywhere: 23 People Who Changed the World by Sarah Prager, Rainey was one of the first singers to sing about women with their own sexual agency, and she sang of having a lover despite being married, of cheating and being cheated on. Rainey was so brashly provocative that, not long after her arrest, she released the song “Prove It On Me,” with lines alluding to her alleged activities such as, “They must’ve been women, ’cause I don’t like no men,” and the song’s promotional ad showed her in men’s clothes flirting with two flappers.

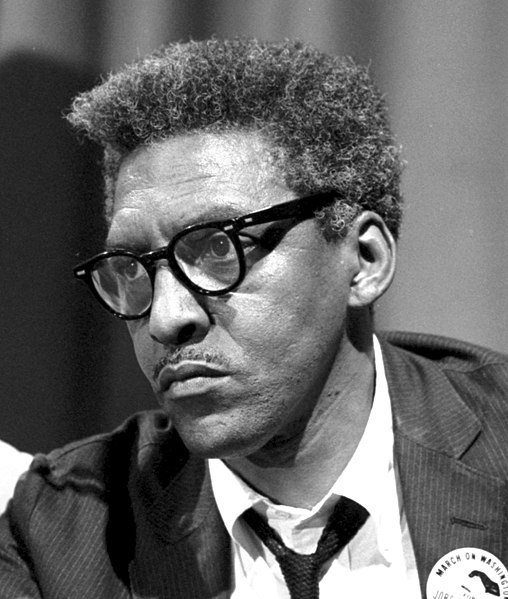

Bayard Rustin was a political activist and right hand man of Martin Luther King Jr. He was also an openly gay man in the 1900s. Police arrested and jailed him numerous times for civil disobedience as well as his sexual orientation, including a two-year stint for refusing to register in the draft. According to the book Queer, There, and Everywhere: 23 People Who Changed the World by Sarah Prager, during World War II, he fought for racial equality in hiring. He organized many political protests around the world, including the famous March on Washington. Rustin was the one to teach King about Mahatma Gandhi’s principles of nonviolence and tactics of civil disobedience. Together, he and King accomplished much, including the Montgomery, Alabama boycott against bus segregation. Rustin also co-founded the A. Philip Randolph Institute, a labor organization for black trade-union members. Rustin’s grandparents raised him. They were the ones who instilled him with Quaker values of equality within a familial unit and supported him throughout his life.

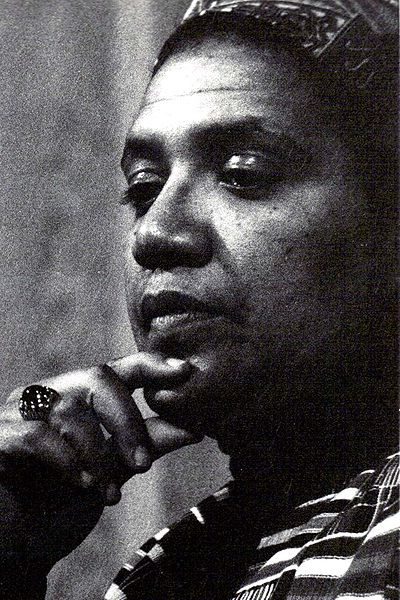

Audre Lorde was a lesbian feminist writer known for her poems exploring black female identity. Her poignant form of social activism contributed towards today’s understanding of intersectionality. As Lorde once wrote, “I have a duty to speak the truth as I see it,” and she did. Lorde co-founded “Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press,” in which they published the writings of other black feminists. She created the Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa in order to address women’s rights in times of apartheid. Lorde died of breast cancer in 1992, after documenting her fight with it for years in her “The Cancer Journals.”

License link: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

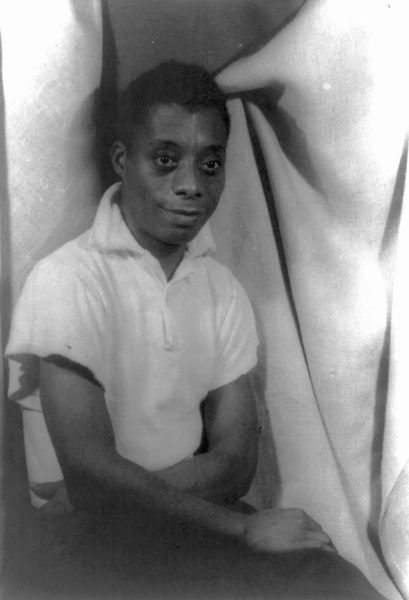

James Baldwin was a writer and activist in the mid-to-late 20th century, whose writings of racial discrimination and homophobia provoked thought, discussion, and growing support for the civil rights movement. Baldwin spent most of his life in France and, after seven years of living there, he published a book about a gay American living in Paris. This book was his jumping-off point for writing about topics that were extremely taboo for the time, such as interracial and homosexual relationships. Baldwin himself was open about his relationships with both men and women and his views on the fluidity of sexuality. He wrote many works, from poems and novels to essays and plays.

Glenn Burke was a gay Major League Baseball player in the 70s who created the high-five with teammate Dusty Baker. Burke played for the Dodgers, almost three decades after Jackie Robinson, and was a down-to-earth and easygoing man. His sexuality was not officially known by the public, but he didn’t try to hide the fact that after a game, he’d go to gay bars in the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco instead of partying with his teammates. Burke said he figured that if he were the best player on the roster, they wouldn’t get rid of him. One year after being diagnosed with AIDS, he said in his 1994 interview with The Washington Post, “I kept saying, ‘As long as I bat .300, and do what I have to do, they can’t say nothing.’” Burke played four seasons with the Dodgers and was well-liked by his teammates. Before the start of the 1978 season, he attended a meeting with the team’s general manager, and Dodgers Vice President, Al Campanis. Campanis put it into simple terms, saying, “Everybody on this team is married but you, Glenn,” and offered Burke $75,000 to get married. According to ESPN, Burke’s response was, “I guess you mean to a woman.” Two months into the season, the Dodgers traded Burke down to the Oakland Athletics for the aging Billy North. Burke played the season with the A’s, where he was a regular starter, but had to sit out the next season due to a neck injury. When he returned in 1980, the team was under new management. Billy Martin, the new manager of the A’s, introduced the new teammates one by one. When he got to Burke, he said, “Oh, by the way, this is Glenn Burke and he’s a faggot.” From then on, Burke grew isolated as his teammates avoided him and publicly distanced themselves. Eventually Burke, haunted by injuries and a demotion to the minor leagues, decided to retire. As he later said to Insider Sports, “I had finally gotten to the point where it was more important to be myself than a baseball player.” Three years later, Burke was in a serious relationship with a man named Michael Smith, who, according to the book Queer, There, and Everywhere: 23 People Who Changed the World by Sarah Prager, secretly wrote an article titled “The Double Life of a Gay Dodger.” Insider Sports ran the article in 1982 without Burke’s permission, and the public found out about Burke because of a man he had trusted. He became the first openly gay sports player, and media sensation, as he went on to play in gay baseball and softball leagues, even winning medals in the Gay Olympics. Bryant Gumbel of the Today show interviewed him on TV, which shocked many people. However, eventually, people moved on and Burke became homeless and struggled with drug addiction until one of his sisters took him in. She tended to him as he wrote his memoir, dictated from his deathbed, until he died in 1995. In his final days, Burke lamented the unwillingness of the sports world to acknowledge his story, or even his existence, telling People Magazine that “It just wasn’t a story they were ready to hear.” However, Burke paved the way for the next generation of athletes to step into the light, such as Jason Collins, Michael Sam, David Denson, William Bean, and many others.

Pat Parker was a lesbian feminist poet in the 60’s who was extremely active in the Civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights movements. She wrote five collections of poetry which frankly addressed topics of sex, race, motherhood, alcoholism, violence and more. Audre Lorde commented on Parker’s style of writing as “clean and sharp without ever being neat.” Parker wrote with personal experience of domestic abuse—her first husband once pushed her down a flight of stairs, leading to a miscarriage. Later in life, her sister’s husband murdered her sister.Parker told the story of her sister’s death in her poem ‘Womanslaughter’. Parker accomplished many things in her life, from pioneering lesbian poetry readings on the West coast and speaking to the United Nations on the status of women to founding the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council and the Women’s Press Collective and directing the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Oakland. Her poem, “My Lover Is A Woman“ is about her life partner, Martha ‘Marty’ Dunham. In the poem, Parker despairs over her community and family’s reactions to her lover’s blue eyes, blond hair and pale skin, writing “& when we go to a gay bar, & my people shun me because i crossed the line, & her people look to see what’s wrong with her, what defect drove her to me …” Parker died in 1989 from breast cancer at the age of 45, leaving behind her partner, Dunham, and their daughter.

Alvin Ailey was a choreographer and a pioneer of modern dance and founder of the world- famous Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, an inclusive modern dance ensemble. Ailey was born in 1931 in Texas to a teenage single mother and moved to Los Angeles at the age of 12. In 1949, he started his Modern Dance training with Lester Horton, and joined Horton’s dance company a year later. Ailey made his Broadway debut when he was 23, and studied dance and acting with Martha Graham and Stella Adler. Ailey formed the Lavallade-Ailey Dance Theater with a group of fellow dancers after recognizing the lack of work for black dancers, and started choreographing his own ballets. His early works did so well that the U.S. State Department commissioned the group to represent the country in a tour of Southeast Asia. Despite Ailey’s suspicions that the government was using a group of black dancers to send a false image of racial harmony abroad, the tour was successful, and after their return the Lavallade-Ailey Dance Theater became formally known as the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. In 1969, he founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center, now known as the Ailey School. Throughout his career, Ailey choreographed around 80 ballets, many widely regarded as masterpieces in the performance world, and inspired by his southern upbringing and experiences with the Baptist church of his youth. He set his pieces to the blues and gospel songs by the likes of Duke Ellington, and with works such as Masakela Language, he explored his South African heritage. Throughout his life, Ailey struggled with mental health disorders, drug use, and being gay in the public eye without being publicly gay. Ailey received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1988, a year before he died of AIDS. In 2001 the AAADT received the National Medal of Arts for their ‘outstanding contributions to dance.’ In 2008, Congress declared them a “vital American cultural ambassador to the world.”

Representative Barbara Jordan became the first woman to ever be elected to the Texas Senate in 1966, and became the first black person from the Deep South to win a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1972. She died in 1996 from pneumonia developed as a complication of her leukemia, after which it became known that she had been in a relationship with a woman named Nancy Earl for over two decades. Jordan served as a Congresswoman for six years before leaving due to a health condition. She spoke at the 1992 Democratic National Convention and Bill Clinton had appointed her to lead the Commission on Immigration Reform. In 1994 she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

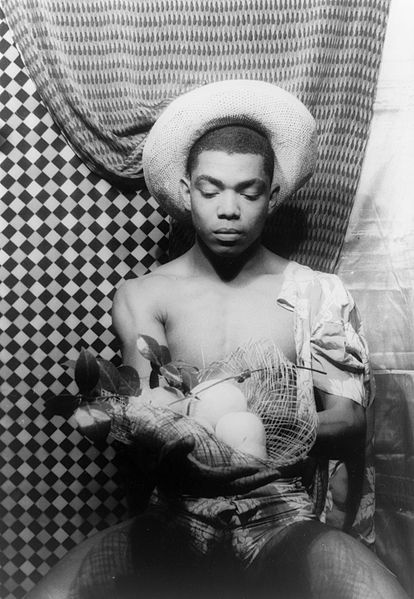

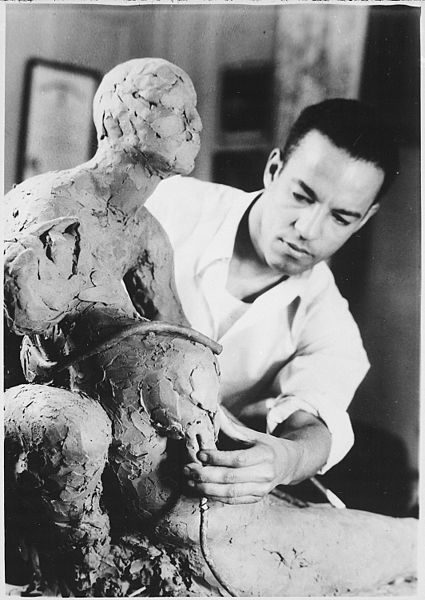

Richmond Barthé was a gay sculptor and painter, and a pioneer of the Harlem Renaissance. He got kicked out from the New Orleans Art School due to his race, and decided to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. His most famous works were celebrations of African culture and the black body, and described the horrors of racial violence and lynching. Barthé created pieces for commission for the U.S. and Haitian governments. He won the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts and numerous other awards.

Lorraine Hansberry was the first black playwright and the youngest American to win a New York Critics’ Circle award at 29 years of age. She wrote the much-acclaimed “A Raisin In The Sun”, an extremely successful Broadway play about the struggles of a black family. The play won many accolades, including several Tony awards. Hansberry wrote for the progressive black newspaper “Freedom” for three years. In 1957, she joined the anonymous lesbian organization, The Daughters of Bilitis, and wrote articles about feminism and homophobia under her initials for their magazine “The Ladder.” Hansberry became active in the Civil Rights movement in 1963, doctors diagnosed her with pancreatic cancer in 1964 and she died less than a year later.