FEATURE: Out like a light

A student yawns during a normal day of classwork early in first block as they prepare to pack-up before heading to second block.

November 22, 2019

Her breathing slowed and eyelids shut before she jerked forward and continued to read the notes on her paper. The battle to stay awake against her own body’s natural instincts became more like war. She checked the time: 12 a.m. As she shook her head and took a deep breath, Manual sophomore, Lauren Baker, tried to cram as much information in her head as possible before her body forced her to shut down for the night.

First to tackle: factoring polynomials. Check for the greatest common factor, multiply the quadratic and constant term, don’t forget any pesky negative signs, cancel out like terms and… Lauren was out like a light. As a top student in her pre-calculus class of mainly juniors, Lauren performed very well on her quizzes and homework. At least when she was not drifting off during class.

Lauren was used to her daily struggle of staying awake throughout the day. She was a high school student after all.

“I have so much going on, so sleep kind of falls off my priorities list sometimes,” she explained. “I sleep when I can, but most of the time, I have homework or something else I have to do that makes it hard to find time for a good night’s rest.”

Although Lauren is used to her sleep-deprived schedule, she cannot help but wonder “is the little amount of sleep I’m getting okay for my health?”

The simple answer is no.

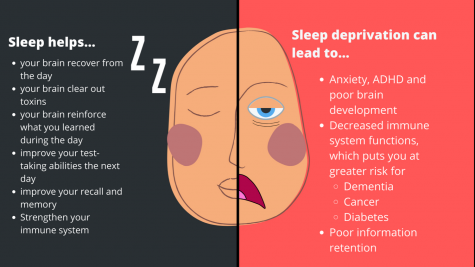

“Sleep is the only time our brain can recover from the day,” sleep specialist and founder of Expert Sleep Medicine, Dr. Robert Karman, explained.

Dr. Karman not only founded his own sleep medicine clinic, but has also made appearances on “Good Morning Kentuckiana” for his knowledge on sleep health. He explained that the small amount of sleep teenagers get is not only lowering students’ performance in school, it is also detrimental to their overall health.

“Sleep deprivation can be the root cause of depression, anxiety, ADHD and poor brain development,” Karman explained.

While Dr. Karman does treat high school students with sleep disorders, he also treats many students with mental health issues caused by lack of adequate sleep. “We believe half the kids diagnosed with ADHD have that because of a sleep disorder and not getting enough sleep.”

Dr. Karman had a specific case of a student with anxiety, and instead of prescribing them medication, Dr. Karman prescribed more sleep.

“I told them to get at least nine hours of sleep for a week, and if they still feel severe symptoms, to come back to me. They told me they felt much better after a week of focusing on sleep.”

In addition to anxiety, depression and ADHD, sleep deprivation can also cause obesity. Lack of sleep can alter metabolic patterns, according to Dr. Karman, which leads to weight gain.

Sleep deprivation not only causes immediate issues for teenagers, but it can also be fatal to their health in the future. Dr. Karman explained that with the little amount of sleep teenagers are getting on average, they are at greater risk for illnesses such as dementia, cancer and diabetes.

“Good deep sleep is the only time we clear waste protein out of our brain. When we don’t get enough sleep, that waste protein builds up to become the plaques and tangles of things like dementia.”

So why are teenagers prone to getting little to no sleep when it can cause these chronic illnesses? Taking a look back to sophomore, Lauren Baker’s, daily schedule explains why.

“I get up around 6:30,” Lauren explained. “Then I don’t get home again until around 5:00 in the evening.”

Lauren’s day consists of school, then a cross country practice from 2:45 to 4:45, leaving her unable to do homework and relax until 5 pm or later. This leads to the question: Is cross country worth getting home so late?

“I absolutely love cross-country. The workouts are fun, and I love my teammates.” Lauren’s eyes light up. “It helps me release the stress from school and gives me something to look forward to in my day. It really helps to keep my mental health in check while I’m stressed out with school.”

So for Lauren, losing cross-country is not an option. She also participates in Y-Club at Manual, which she goes to every Thursday.

“With my practice schedule, it can be hard to fit everything I need to do into my week,” Lauren explained. She has practice five days a week, with Fridays and Sundays off. “We choose one of our off days to run on our own, too. I run about six days a week.”

Just like Lauren, 57% of high school students participate in sports, clubs and other extracurricular activities after school hours, according to the United States Census Bureau.

“I’m exhausted by the time I get home,” she said. “With homework, I barely have time for a break to relax or play on my phone.”

Lauren’s cross country practices have a range of effects on her body, depending on the weather.

“We practice in any weather mostly,” she explained.

Running in the heat causes a depletion of fluids and electrolytes in the body, leading to reduced blood-flow, which causes a runner to feel exhausted after their run. Athletes are not only tired after a hot day’s practice, though. With proper hydration and cool temperatures, athletes still feel the need to go to sleep after their practices. Consider it math: sleep deprivation, plus a seven hour day of brainpower and a hard workout, equals a pretty exhausted teenager.

Something to note about this feeling of exhaustion is that it is completely natural. As a teenager’s body develops, it requires more sleep for normal bodily functions, such as protein cleanout and strengthening the body’s immune system.

“Teenagers require eight to nine–closer to nine, hours of sleep per night,” Dr. Karman explained. “If you have one night of five hours or less of sleep, your immune system function goes down to 30% of what it should be.”

With the average teenager only getting around six hours of sleep, and 87% of teenagers being chronically sleep deprived, the health and well-being of high school students is in great jeopardy. So why won’t teens go to sleep earlier? How much of this issue is really their fault?

According to Dr. Karman, none of it.

“It’s all about the way we’re wired,” he said. “When we are teenagers, we have this delayed sleep phase. So, the natural time of our circadian rhythm is programmed that we don’t want to put our head on the pillow until 11:00. But by the way, we want to sleep in until 8:00 or 9:00. It’s just our programming and wiring,” he explained.

With his 25 years in sleep studies, Dr. Karman strongly pushes onto school districts how school start times negatively affect students’ health.

“We are getting our younger people up for high school at a point and time where they would much rather be sleeping later.” Dr. Karman sat up in his chair. “Our school start times should be 8:30 or later. There’s clear information and data on better high school performance, completing high school, less traffic and accidents and a whole bunch of amazing things if we started school later.”

Regardless, high school students in Jefferson County Public Schools still hit the books by 7:40 in the morning.

Dr. Karman explained the struggles he has encountered when talking about this problem with Kentucky’s own school districts.

“Here in our region, I’m fighting with Jefferson County that doesn’t [move school start times]. I know it’s all about transportation and the bus drivers and things, but little kids can get up a lot easier than teenagers and should go to school earlier.”

So if sleep is so important to students’ health and studies, why is it not prioritized by school districts?

“The education is critical,” he explained. “It’s presenting and in a way where we are all on the same page. We need to understand how important sleep is.”

Dr. Karman believes that sleep education should be required in health class just as other topics such as mental health, diet and exercise.

“I think we should devote the same time to sleep that we do with diet,” he said. Dr. Karman believes requiring sleep education in schools can teach students like Lauren how much sleep can affect not only the health of students, but their studies, too.

“The way that we reinforce learning is actually when we’re asleep,” Dr. Karman explained. “There was a neat study done a couple years ago where a concert pianist was practicing a piece on a keyboard.”

Dr. Karman then explained the science of the study, where the pianist was in a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which is a type of imaging test. The device scanned the pianist’s brain, and told the scientists which cells were active by looking at glucose uptake, or where glucose enters inside cells by receptors located on the cells’ surface.

“So as this guy is practicing his piece on the piano, you can see parts of his brain lighting up. They then have him put the keyboard down, lay in the scanner, and go to sleep. And as he goes to sleep, the same sequence lights up as if he were playing that piece.”

PET scans have been used in numerous studies to help scientists understand exactly how the brain learns and retains information.

“So that gives us the concept of learning and rewiring those tracks of learning. A critical part of us learning is getting enough sleep and reinforcing those tracks,” he concluded.

So how can this information help students like Lauren to get more sleep at night? To Dr. Karman, it is priorities and facts. Because of the studies done proving that the brain reinforces information we have learned during sleep, “we can show there’s a 15-20% improvement in test-taking skills, abilities, recall and memory with adequate sleep,” Dr. Karman said.

Making a list of priorities in order can help students to know when to keep studying and when it is better to call it quits for the night.

“There’s a balance,” he explained. “When it comes to homework, since I’m the sleep guy, I’m going to say sleep [is a higher priority.]”

Dr. Karman said that it is better for teenagers to shut down for the night when they feel their eyes start to get heavy.

“It’s much better to wake up in the morning to get your work done, than do it poorly when you’re exhausted.”

If more teenagers knew this information, fewer would be falling asleep on their books, as Lauren did the night before her math test.

“Lauren, it’s almost time to go!” her mom exclaimed as Lauren pulled the covers over her head. Slowly sitting up, she slouched in her bed and stared at her blanket for ten minutes before finally getting herself moving. She stumbled out of bed to her closet, where she threw on the closest outfit she could find. Wiping her eyes, she found her shoes and walked to the restroom to brush her teeth. The splash of cold water on her face made her eyes widen for only a second before drooping back down to their half-open position. Lauren threw her shoes on, and it was time to leave.

She took notes in silence in her first class, world history. While Lauren was alert, the student behind her dropped his head onto his textbook where it remained until the sound of the bell.

“That class makes me so tired,” Lauren said as she stretched her arms and yawned. “Having it first block makes it so much harder, too.”

Walking to her second block, Lauren remembered her test. “I think I’m ready,” she said. “I’m just worried I didn’t have enough time to study.”

When arriving at the class, Lauren took her usual seat in a table of her friends. They talked about the topics of the test for a few minutes, then it was time to start. Lauren wrote quickly, finishing the first few problems without much struggle. But as the test went on, Lauren’s eyes grew heavy, and her pencil stopped moving. Her head bobbed up and down along with her eyes, and Lauren started to doze off before she jerked back awake and continued to solve the problems on her paper.

She fought to stay awake and remember what she had studied the night before. Factoring polynomials: check for the greatest common factor, multiply the quadratic and constant term, and Lauren was out like a light.