BHM: My grandpa’s experience with busing

On Aug. 15 2019, administrators watch buses arrive to school in the morning. JCPS’s busing policy, implemented in the school year of 1975-1976, provides busing for any students living more than a mile away from their school. This practice attempted to desegregate the city.

February 26, 2020

In July of 1974, the Supreme Court ruled on Milliken v. Bradley, one of the most influential court cases on school desegregation. While Brown v. Board of Education decided that “separate but equal” schools were, in fact, not equal, Milliken determined how school districts should be desegregated. Most notably, it allowed the practice of busing.

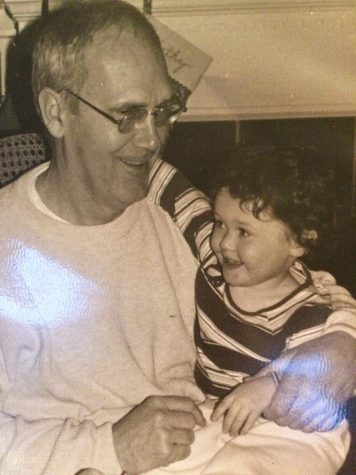

Just one year prior, my grandpa, Taylor Jarboe, began his 27-year teaching career in JCPS.

“I taught at Parkland Junior High School for three years. I could say that I taught at two Parklands, the all-black Parkland before busing, and the integrated Parkland. Both were very good schools,” Jarboe said.

Busing was an inflammatory topic for several reasons. It aimed to solve the greater issue of Louisville’s segregation within schools. In addition to that, the Louisville Public School District and JCPS merged as they implemented busing. Biases against the Louisville schools also sparked controversy.

“There was a general feeling that the Louisville school system was inferior to that of the Jefferson County system, and so it was not surprising to find that many parents that lived out in the county held the belief that their children would be attending schools with inferior facilities, administrations and teachers; in short their children would receive an inferior education. Add the racial component to that and the odds of this social experiment being successful were fairly low,” Jarboe said.

During busing’s first year, the now-unified JCPS underwent a world of change, and the people on the frontlines of that change were the teachers.

“Teachers, by and large, are humanitarians. They love the art of teaching and love their connection with students. I believed that if the busing experiment were to succeed, it would rest with the teachers, but in looking back my general feeling is that everyone involved—administrators, teachers, and students—for the most part wanted this to work, and worked doubly hard to make the classroom environment not only academic, but humane and empathetic,” Jarboe said.

After the inaugural year, Jarboe transferred to Central, a historically all-black high school. Many students and alumnae were proud of this heritage and resented losing that identity. These feelings were shared with alumnae and student bodies of other historically black and historically white schools.

“These resentments, at least in my opinion, were a small price to pay for what I consider to be the greater good, an attempt to bring blacks and whites together in a community that was suffering and still suffers from segregation,” Jarboe said.

And there certainly were resentments.

“Perhaps the most vivid and longest lasting memories are the ones that happened outside of the classroom. I recall the anger and disbelief I felt when watching the local and sometimes national television news showing footage of black students on buses entering white neighborhoods, with the streets lined with white protesters chanting hate, carrying signs of hate and worst of all throwing rocks, bricks, bottles, anything they could get their hands on at buses filled with young black students,” Jarboe said.

Though he observed moments of humanity often within the walls of the school, like the one shown in this Courier-Journal photo taken at Greenwood Elementary, my grandpa still worries how those students ended up.

“Imagine the horror these young children endured being pelted with bricks and stones, and I still wonder today if the emotional and psychological scars from these on-the-bus incidents lasted a lifetime, and I wonder if these children, when they grew up, were strong enough to overcome these indelible acts of hatred. I wonder if they were able to forgive, or if the resentment and mistrust and enmity still linger,” Jarboe said.

While my grandpa observed black students being bused mostly on the news, he was a first-hand witness of white students being bused to Central.

“While the white students being bused to the inner-city schools were not greeted with bricks and bottles, they nevertheless experienced a great deal of fear and anxiety as well,” Jarboe said.

In spite of these issues on the outside, what my grandpa witnessed in his classroom gave him hope.

“The vast majority of our students, black and white, seemed willing to give this experiment a chance. There were those who came with terrible attitudes, and some remained bitter throughout the year, but most were willing to make the best of this experience,” Jarboe said.

Despite the best efforts of the district, teachers and students, there’s no denying that Louisville is still segregated; the effects of redlining still exist, along with lingering seeds of white supremacy.

“Nearly 50 years later, we’re still struggling. I remember well the horror in 1964 when three civil rights workers were killed in Neshoba County, Mississippi, while working to register black voters thanks to a recently passed Civil Rights Act that guaranteed, among many other things, the right for all citizens to vote. And today, Charlottesville, Virginia, is still fresh in our minds, when a young woman was run down by a car driven by a white supremacist who never learned to walk around in someone else’s skin. The genetics of hate and racism prove stronger than the grave. And yet, we have made progress, slow and inexorable, but how tiresome it is,” Jarboe said.

Though it may seem exhausting and, at times, fruitless to continue fighting for justice and equality, it’s a necessary struggle. 20 years after my grandpa’s teaching career ended, he still has hope for Louisville’s future.

“As for the Jefferson County Public Schools today, let’s give them credit for their concerted efforts to maintain integrated schools. I’m unaware of any studies that have researched long-term effects of busing on educational achievement, but it’s hard for me to believe that returning to segregated schools is an option that this community really wants or needs. The integration of our schools is perhaps our last and best hope, as Louisville still remains a segregated city. I believed then, and maintain the belief now, that despite the flaws and expenses of busing, integrated schools are the cornerstone to a greater society,” Jarboe said.

Featured image taken by Mandala Gupta VerWiebe.

Amy Griffith • May 21, 2023 at 4:02 pm

Mr. Jarboe made such a big impact on me and my peers at Central, Class of 88. We were a squirrelly bunch and I was a mess. I hope you still have him. Tell him I made it! Successful career in mental health. Love, Amy Griffith

LeAnn Phelps • Jan 8, 2023 at 2:48 am

1996 CHS graduate here and your grandfather was probably the first teacher to believe in me as a student. I entered Central on probation and due to his belief and passion in teaching I ended up graduating at the top of my class and in advanced classes. He had a genuine talent for making education fun. I literally remember him biting on his glasses and his hand gestural motions as he taught class. I watched him cry as my class walked to get our diplomas in June of 1996. He lit a fire inside me a young student that has never died. He is the sole reason I was able to write a proper paper in college and he made education a life long passion of mine. I will forever be grateful ? if he is still with us send him love from Leann Phelps..

Chloe Autumn • Mar 16, 2020 at 11:52 am

Mr. Jarboe was my humanities teacher 1993-94 as well as the newspaper sponsor throughout my four years at Central. My daughter and I were discussing a research paper she is working on and it reminded me of a paper I wrote my senior year in Mr. Jarboe’s class. A quick Google search of his name and I stumbled across your article. He was one of my favorite teachers, but I am sure I never told him. My final year at Central was wrought with racial tension. I enjoyed reading his insights in this article. How I wish I had heard more of them first hand when I was his student. Tell him my family still watches CBS Sunday Morning thanks to him!

Gregg Bennett • Feb 29, 2020 at 8:34 pm

Your grandfather was a very enthusiastic and compassionate teacher. I was bused to Central from Eastern in 1979-80. Your grandfather was also my football coach. My first year (1979) as a junior was very much a ‘melting pot’ of students from all over jefferson county. Everyone seemed to get along because we were all in the experience together. Even in 1979 I can remember having to leave away football games in all of our equipment as we sat on the bus because of the possibility of someone throwing something at the bus. I don’t feel that I’ve carried any resentment from those times. People (adults) seem to fear the things they don’t understand and would rather fight against the unknown then take the time to learn about it. But I do think and hope the generations after this period have become more compassionate.