BHM: Alums reflect on Manual’s adaptation to Brown v. Board of Education

February 26, 2022

In 1954, the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education reshaped the education system for schools across the country. It required the integration of Black and white students in public schools, stating that their segregation violated the fourteenth amendment. Following this ruling, some schools began to integrate far sooner than others, and Manual was no exception.

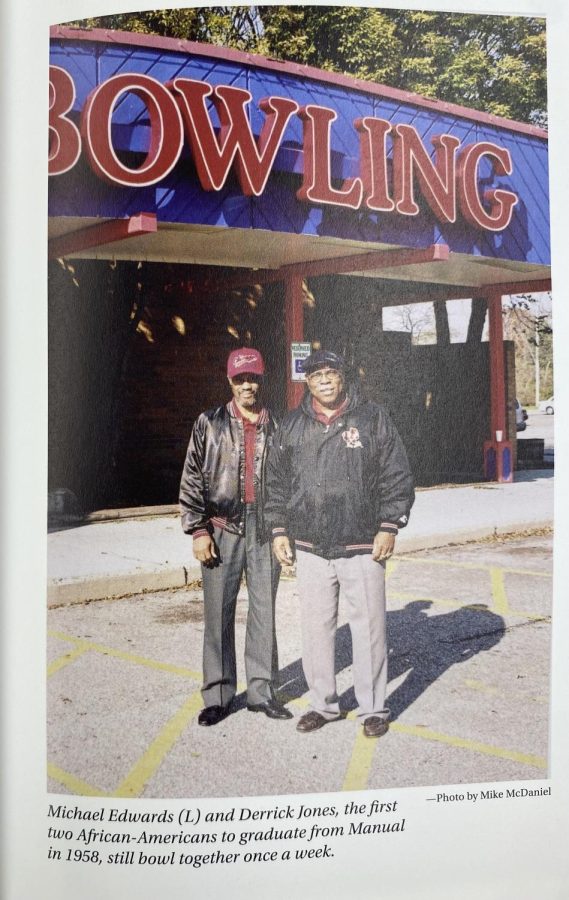

The integration began in 1956. Derrick Jones and Michael Edwards, Manual’s first Black graduates, enrolled that year and graduated in 1958. Jones and Edwards still bowl together every Saturday.

The integration at Manual took place soon after the merger with Louisville Girls’ High School (now Male High School) in 1950. Many changes were taking place within the school. Before there was a divide between Black and white students, there was a rift between male students and female students. This divide between boys and girls ripped through even the class graduation requirements: girls were required to take home economics and boys took mechanical electives.

Phil Bond, a Manual alumni from the class of 1972, recalls his own experience taking mechanical electives. Mechanics were not his area of interest– he preferred literature and English– but this did not hinder him from graduating third in class. In addition to his academic excellence, he was heavily involved with Manual’s basketball team. He was one of the top ten athletes in Manual’s history. Current Manual students can observe Bond’s legacy even now, as his jersey (number 21) hangs in Manual’s halls.

For some, Manual was their first impression of attending an integrated school. Wilber Hackett, class of 1967, reflects on this experience: “I really didn’t know what to expect, but it went relatively smooth . . . No real issues until I got into playing sports and there became issues,” Hackett said.

Manual did not become a magnet school until 1984. Before then, students could make the choice to attend Manual without going through the admissions process. Hackett made the decision to attend Manual based on the school’s academic standing, alongside the sports programs that he was deeply invested in, such as football, basketball and baseball. Hackett distinguishes that his high school experience only represents him individually. Being an athlete gave him an upper hand that he did not recognize until talking to a peer after graduation.

“I was an athlete, and quite frankly, pretty much a starting athlete. I didn’t run into some of the issues that some of my other Black students experienced. So actually, I talked to one of my teammates later on in our lives, and he was saying he didn’t feel comfortable with Manual initially,” Hackett recalls.

He was telling me about how he felt that some of the white people at Manual didn’t feel like they wanted him there. And I said, ‘well I didn’t feel that bad about it.’ But then he said, ‘you were the star, so you didn’t even deal with some of the issues I had to deal with.’

— Wilber Hackett, c/o 1967

Hackett felt he could play to his fullest potential, but did notice a divide. He discussed an incident that occurred after a football game and involved the principal at the time

“There were some white female students who were pretty friendly to some of the Black athletes. At one point at Manual, the school principal, called two, maybe three, young white girls to the office and told him that they were being overly friendly to us, and discouraged them from being friends with us. As a matter of fact, one of the young white ladies was a cheerleader, and they took her off the cheerleading squad because she was too friendly with the Black athletes,” Hackett said.

Hackett’s active participation at school reflected in his community. He marched with Martin Luther King Jr. down South 22nd Street and West Oak Street to Broadway when the latter was in Louisville. Hackett recalls a moment that stood out to him as he listened to MLK give a speech.

“One of the things that was so disappointing: I couldn’t see faces, but I saw letter jackets of students from Manual High School and Male High School, where they were throwing rocks and balls at us,” Hackett said.

Ralph Emerson, class of 1969, references to the significant number of historical events during his time in school. “It was a very tough period from 1967 until about 1972. Dr. King died in ‘68, there were riots, we had marches in the city, there’s open housing demonstrations, there were lots of issues going on,” Emerson said.

When regarding his class, Emerson fills with pride as he notes various accomplishments, especially those of his fellow Black peers who made up less than five percent of their graduating class.

“Half or more of the leadership positions in the class were African American; our homecoming queen was a Black girl; the drum major of our band was Black; many of our football players and the majority of our basketball players were black; and we’d only been at the school a short period of time. I was the first Black person to be elected student body president, but following me was Danny Woo, and Danny was a Chinese American kid. I think he was probably the first Asian American kid to be student body president at duPont Manual,” Emerson said.

Furthermore, Emerson and his class were also able to implement an African American history class to Manual, which is still taught today. He hoped that African American history would be further discussed, rather than underrepresented, through prominent figures in the movement. The impact that Hackett, Emerson and Bond, left on Manual still stands today.