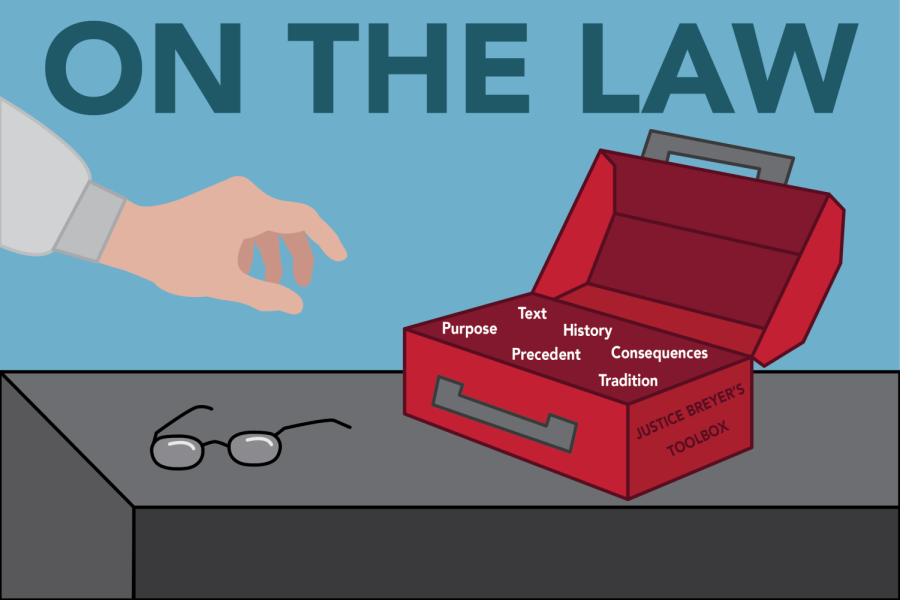

On The Law: Justice Breyer and his toolbox

Justice Breyer utilized lots of legal tools in his time. Graphic by Molly Gregory.

April 26, 2022

Justice Breyer, the famed Supreme Court Justice will retire at the Supreme Court’s end of the term, typically in June. With his leave, there comes a new wave of statutory construction and constitutional interpretation.

It is now said by many within the legal community that, “we’re all textualists now.” Plainly, I disagree. But first, I think it’s important I go over the various aspects and ways in which judges and lawyers look at the law, and how those interpretations affect the everyday life of the American people.

First, we must establish that there are two main philosophical thought processes on statutory interpretation (the way we interpret laws written by Congress). Those two main ways of thought are: textualism and purposivism. On one hand, textualist looks at the plain meaning of the text. And to find such a meaning, they will use contemporary definitions of the words used within the text and what those words meant when the text was adopted. On the other hand, there are purposivists. Purposivists have a broader way of looking for answers within the law. Purposivists look at, of course, the purposes of the laws, the intent of those who made the laws. To find those intents and purposes, purposivists use Committee Reports (summaries of the laws passed by that committee given to members), floor statements of those who had great input on the passage of the bill, and so forth.

There is a clear divide here, and of course, the legal community as it pertains to statutory interpretation is divided. So, you may be thinking where I lie on this issue. Now, I shall explain my thoughts on the matter.

A few days ago, I read the Supreme Court decision in Badgerow v. Walters. The Supreme Court in an 8-1 decision, decided a statutory matter regarding federal court jurisdiction with respect to arbitration cases. Believe me, you need not understand the case in its entirety to understand the argument for which I am about to make.

It is my belief that the purposivist view is one that makes our democracy work and would best promote the democratic values of the Nation when judges are the most politically disconnected from the people. The people elect our legislators, who in turn write and pass our laws. Judges, on the other hand, are tasked with interpreting those laws and they reach those decisions based on logical conclusions.

As I explained earlier, purposivists use a broader range of tools to get their answers than textualists. I prefer that approach. While textualists believe the meaning of text can be found merely looking at the plain meaning of words, through tools such as dictionaries and thesauri, I don’t believe we can uphold a democratic system by interpreting laws passed by Congress “in a vacuum.”

When lawmakers make laws, the words must be agreed upon by both houses of Congress and be signed by the President. When Congress makes laws, they are usually intending to fix a problem within the country. Generally, with language, there is an intent to the writing. Say that there is a big voter suppression problem within the country and Congress writes a law to fix that problem, there is of course an intent by Congress to fix that problem with the words that they use. And that intent matters when the words they use are not so clear. If you’re trying to discern the meaning of a text, wouldn’t it help that the context and reasons from the people who wrote those words matter? Or rather, for my textualists friends, why doesn’t it matter? Would it not be better for Court to defer to the legislature—the one’s closest to the people—when interpreting the words that they wrote? Would that not uphold democratic values, and connect courts closer to the people? Purposivists look at this very intent by many means, as mentioned earlier. Looking at Committee Reports give both legislators and courts an idea of the intent of such a law. For example, committee reports explain what the law does, how it will be implemented and what specific words mean within the statutory context. Further, floor statements from prominent members of Congress also give key insights of what laws truly mean. Though floor remarks can often be the broad strokes within legislative drafting, they are still helpful in trying to find a meaning of the law that was passed.

Further, purposivists look at the very real consequences of the possible interpretations. If an interpretation of a law results in more legal ambiguity than was once thought, it need not be accepted, even if such an interpretation is the most “textually” based. In doing so, courts are looking at not just the present, but the future and preventing the courts from taking a potentially dangerous course of action. Looking towards the consequences can give courts a unique insight on how to further develop interpretations of the said statutes. They need not be afraid to look at those consequences because those consequences are those that the American people are going to face and thereafter accept within our tradition of upholding the rule of law in the United States.

My argument is not to say that textualists do not have a point when interpreting statutes that are clear and have an obvious meaning to them. But, my point also shines a sharp disclaimer on that point. The text is almost always ambiguous, especially when the circumstances of the dispute can provoke second thoughts on the interpretation. Yes, the words of the Constitution are clear when it says that only those people who are 30 years old can be Senators, but what it not so clear is the meaning of what a “tangible object,” is when the Supreme Court decided Yates v. United States. Those questions are much, much harder, and it only makes sense for one to delve into the legislative history of the text to truly understand what the Congress means when it says “tangible object.”

There are a few take-aways I would like noted here. First, by no stretch of the imagination am I the least bit qualified to speak on the topic of statutory interpretation, but I do think there are certain considerations we should using to ascertain the meaning of the words Congress has passed. If a law is not ambiguous, the text overrides any sort of legislative history or intent seeking. But often time, the text is ambiguous, and therefore, we should use extratextual tools to gather the meaning of text passed by Congress, and uphold those democratic principles

As Justice Breyer prepares to step down, his legacy will be remembered as a justice more likely than not to fulfill the democratic principles that our Constitution. As he said in his most recent dissent, “we should interpret those words ‘with reference to the statutory context, structure, history and purpose . . . not to mention common sense.’”