OPINION: The displacement of Muslims’ voices in France after the French Election

Emmanuel Macron, left, and Marine Le Pen faced off in the 2022 French Election. Photo courtesy of NBC News.

May 15, 2022

The tight presidential race between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen drew in an audience that spanned beyond just France. The election was a momentous one for Le Pen in spite of falling shortly behind Macron. In this election, Le Pen attracted a higher percentage of voters than any of the three previous times she ran.

Emmanuel Macron represents the center-right En Marche party. Marine Le Pen represents the National Rally, a party founded by her father, who rooted it with anti-Semetic language, something Le Pen has tried to erase through her campaign.

Le Pen removed her surname “Le Pen” from political posters and simply went by “Marine”. The beginning letter of her name, “M” is similar to the sound of the word “love” in French and has created a new pun among voters. Going from “Marine Le Pen” to “M La France”.

The racist history of the National Rally is clearly evident by the tactical choices Le Pen has made in her campaign, but not all her strategies are new ones. In a 2014 interview, Le Pen expressed, “I do not stop repeating it to French Jews… the National Front [is] not your enemy, but it is without a doubt the best shield to protect you. It stands at your side for the defense of our freedoms of thought and of religion against the only real enemy, Islamist fundamentalism.”

The acknowledgment and removal of anti-Semtic language are beyond important however, the manner in which this is becoming problematic. Le Pen rallies on dividing two religious groups that are infamously known for religious tensions aside from French politics. Yet, by ridding of her father’s antisemitism she also opens a new chapter of fear: Islamophobia.

Muslims make up 5.6 percent of the population in France. Despite the number seeming like a fraction of a majority, they are also one of Europe’s largest Muslim hosting countries.

The fear of Muslims and their religious beliefs have continued to grow with laws directly restricting their religious freedom of expression. In turn, the environment for Muslims in France has become increasingly more difficult.

France’s secularism, known more frequently as “laicite”, discourages religious involvement in government. France has been a secular nation since 1905, separating church from government. Therefore the separation between religion and politics is implemented for all. Although, the enforcement imposed upon Muslims seems to raise questions of a double standard.

During Macron’s term in office, the French National Assembly passed the anti-separatism bill despite opposition from the right and the left. The bill was implemented in response to the tragic killing of Samuel Paty, who depicted the Prophet Muhammed in cartoon form, an offense to Muslims that traditionally do not draw the physical face of any prophets, which sparked a need to reinforce “Islamist forces” in France bringing about the bill less than a year later.

The bill was meant to extend “neutrality” in the workplace that prohibits religious symbols such as the headscarf for Muslim women. However, by the separatism law imposed by France, it would be in more accordance to remove all acts of faith rather than the singularity of Islam.

The call for Muslim voters is little to none. Candidates, like Le Pen, don’t bother putting on a show to receive the support of Muslim voters. Instead, Muslims become campaign weapons to trade around, dehumanizing their need to select from the lesser of two evils.

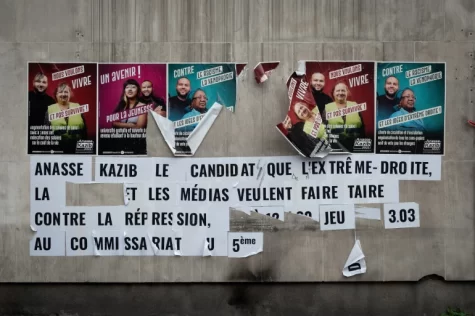

Some, like Anasse Kazib, a Marxist-railway worker, are not being passive with their actions in being a voice for Muslims. Kazib ran in the first round of the French Presidential Elections but did not meet the 500 sponsorships that he needed and said the reaction to his campaign met with hostility and fear.

“There were posters of my face in Paris, with the words ‘0% French, 100% Islamist’ written on it. When you’re a political activist you don’t have the right to be Muslim, or even Arab,” Kazib said.

For Muslims in politics, the root of their initiatives is not fueled by the need to spread religion but rather the need of being heard. If anything Muslims draw in the morals from their religion, such as kindness, acceptance, and justice. These morals are not aligned with a spread of their religion but rather guidance as it would be for any other presidential candidate still practicing their faith of choice.

France’s presidential debate took place during election week, only four days before citizens went to the polls and cast their ballots.

President Macron has publicly supported the anti-separatism bill that banned the hijab (religious head covering worn by Muslim women) for Muslim girls in schools under 18. Yet, during the debate, he criticized Le Pen’s plan to outright ban the hijab from all public settings, asserting it would trigger a “civil war”. A contradicting claim considering the law Macron imposed in the means of secularism.

“I believe the headscarf is a uniform imposed by Islamists that most young women that wear it have no choice,” Le Pen said in the televised debate.

For Le Pen eliminating the headscarf is a means of shielding young Muslim women from oppressive forces. However, this enforcement eliminates the power of choice. The current invasion of Afghanistan by the Taliban demonstrates the elimination of choice in an opposite manner. Under their control, women are forced by law to wear the burqa and hijab, in turn, a Muslim women’s power of choice, is also eliminated.

To many Muslim women, it is the ability to make that decision for themselves, wearing a hijab or not, that is what holds the “true” value in their actions. Restricting the hijab and forcing it upon women and young girls destroys the sense of religious choice.

Macron’s win was not a surprise to many, but it did not make it any less historic or any less unsettling, especially for French Muslims. But the podium still shines on Le Pen and Macron, even after the conclusion of the election. The means of how their campaigns drew out and the matters of beliefs becoming liable options for law are baffling, especially when it stems from a fear of the “other.” Muslims like Assia Belgacem know that the political environment will not change in the near future.

“I know what they’re saying about me and the likes of me. I know that because every five years it’s the same rhetoric,” Belgacem said.

Instead, the fight is singular, where they reside in a place that no longer feels like home. With restrictions to their place of worship, anti-Islamophobia organizations shutting down and just their image criticized to an unrestricted extent, the question of when remains. When will being Muslim and French be okay? Or will France reform its own version of Islam that becomes a shard of the original?