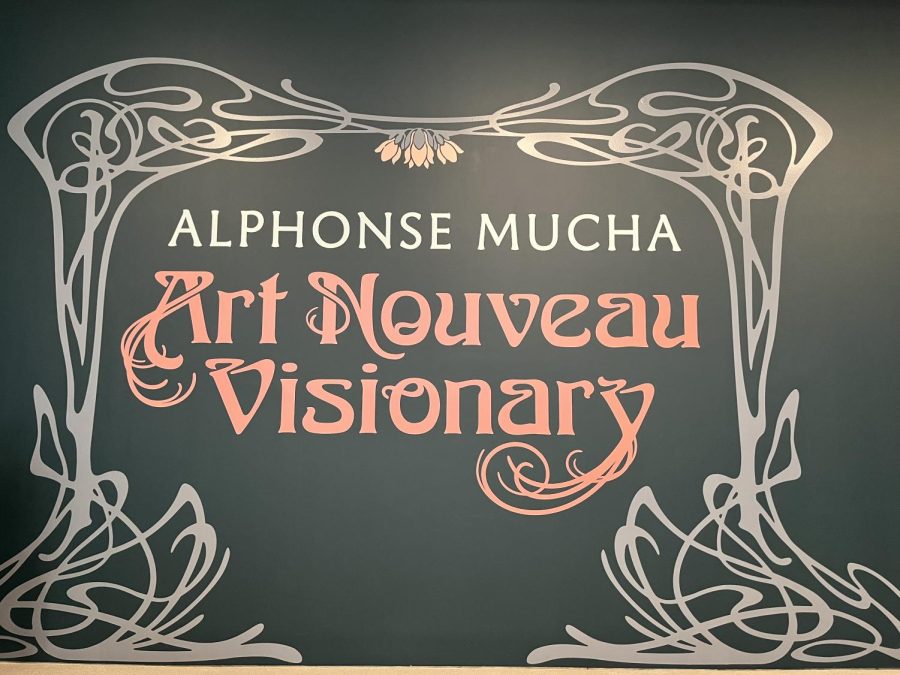

Speed Art Museum features the artwork of Alphonse Mucha

The entrance to the exhibit.

February 10, 2023

The collection of Alphonse Mucha traveled to the United States for the first time in 20 years from Oct. 21, 2022 through Jan. 22, 2023 at the Speed Art Museum’s exhibition “Alphonse Mucha:

Visionary.” Visitors were able to view many of his famous works and even drafts and sketches showcasing some of his early concepts.

Visionary.” Visitors were able to view many of his famous works and even drafts and sketches showcasing some of his early concepts.

Mucha was a prominent Czech artist during the late 1800s and early 1900s and was a part of the Art Nouveau movement. His work focused around the female figure, which he incorporated into many of his infamous movie posters and advertisements. His style featured an expert understanding of the human figure as demonstrated by the unique positions the limbs of his subjects were angled into and expressed a revitalization of his native Czech culture.

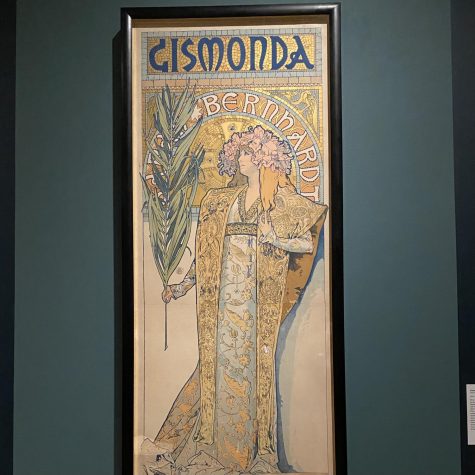

Mucha began as a struggling artist but got his big break after he received the opportunity to design a poster for French actor Sarah Bernhardt in her title role in the theatrical piece Gismonda. The poster he created was plastered around France, which prominently featured Bernhardt in full costume.

“The people of Paris loved it. It was absolutely revolutionary. It was unlike anything anybody had ever seen before but in an extraordinary way,” Speed Art Museum curator Kim Spence said during a tour of the exhibit.

Mucha then became Bernhardt’s full-time artistic director, designing her stage sets, costumes and jewelry.

“They developed this incredibly collaborative relationship that not only bolstered her career but gave Mucha incredible fame,” Spence said.

This was largely due to Mucha’s unique style. His posters would consist of two separate poster papers glued together to enlarge the scale, giving the subject of his artwork a more lifelike feel as they were almost life-sized. It looked as if they were about to step out of the painting and onto the streets of France.

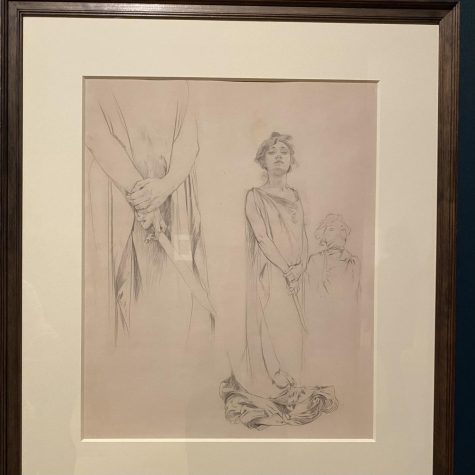

In his poster for the film “Médée,” Mucha displays Bernhardt standing above the body of a child wielding a bloody dagger, the climax of the film. “Médée” is a modern adaptation of a Greek tragedy where Jason’s wife, Médée, slaughters her husband’s children and lover after he leaves her. The poster expertly depicts the subject’s utter shock as the whiteness of her eyes stares right at you, and the distorted figure of the child lying below her feet creates an uneasy feeling. In the exhibition, they even showcased a few of his sketches and preparatory drawings he created before the final poster.

While Mucha initially gained fame for his work for Bernhardt, he also dabbled in product advertising.

“Oftentimes he would create a character that came to embody the product brand,” Spence said.

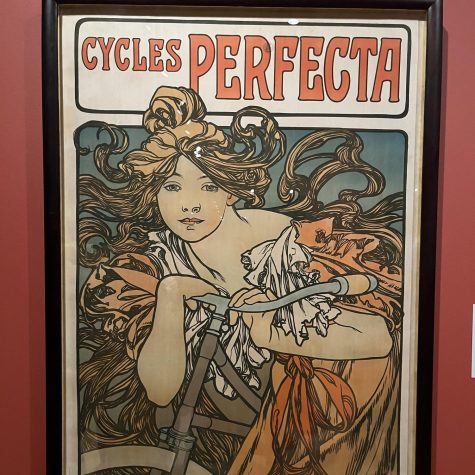

While many advertisement posters of the time prominently featured the product they were trying to sell, Mucha’s advertisements did not. Instead, Mucha’s artwork would sell an experience, as illustrated in his poster for the bicycle brand Cycles Perfecta.

The character he created has long blonde hair as if it had been blown by the wind. Her arms are draped over the handlebars, and she’s leaned over. These techniques convey her emotion as it looks like she has just finished an exhilarating bike ride, thus expressing the experience of the bike.

The exhibit also featured some of the actual product packaging that Mucha designed, like a perfume bottle and biscuit tin.

Additionally, the exhibition displayed pages from Mucha’s book titled Decorative Documents, which was essentially a guidebook for artists who wanted to take inspiration from his unique style. Mucha created the guidebook after he became bombarded with commissions and didn’t have the time to accept them all.

Mucha became so renowned that the Austrian-Hungarian empire commissioned him to design the interiors of one of their pavilions in the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Near the end of his career Mucha embarked on the biggest project of his career, the Slav Epic.

“Mucha himself had considered it to be the greatest work he ever created,” Spence claimed.

This project is a series of 20 paintings, towering as tall as 26 feet. It showcases a timeline of Czech and Slavic history in picture form. Unfortunately, this epic was not displayed at the Speed, as the paintings are much too large to fit inside the exhibition. The Slav Epic currently resides in Prague. However, the Speed was able to project a slideshow that showcased some of the paintings in the epic.

The exhibition helped illustrate Mucha’s distinctive style and impact on European art at the time. His understanding of the human figure as well as his blend of muted colors became revolutionary for its time. As a native Czech man, Mucha was able to express cultural aspects of his home through his posters and designs.

“Mucha is so much more than a commercial graphic designer. He had these underlying philosophies about what art should be and the role that art should play,” Spence said.