“I just feel like I cannot be myself in Kentucky”: Trans Manual students speak out

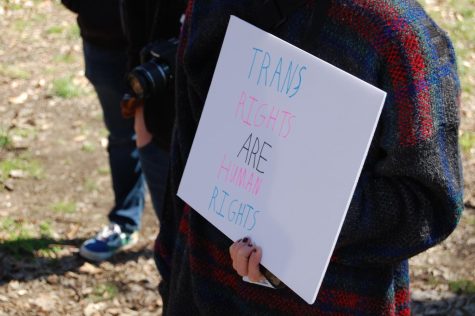

In the wake of an omnibus anti-trans bill passing the Kentucky Senate, students rallied in Central Park. Photo by Gael Martinez

April 4, 2023

If you or someone you know needs trans peer support, you can call Trans Kentucky at 859-448-5428 or visit transkentucky.com. Nationally, you can call the Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860 or visit translifeline.org. LGBTQ+ youth can get support from the Trevor Project by calling 866-488-7386 or visiting thetrevorproject.org.

On an early spring Monday in the middle of March a small crowd of students, parents, teachers and news anchors gathered in the southeast corner of Central Park, a six minute walk from the YPAS annex of Manual. Everyone wore coats in neutral grays, blacks and greens to combat the chilling wind. But bright pops of color from rainbow flags or signs made in the baby blues and pinks of transgender pride stood out throughout the crowd. Some wore blue and pink pencils on their ears that read “Protect the rights of transgender children in Kentucky.”

This small gathering was in the wake of the Kentucky General Assembly’s passage of Senate Bill (SB) 150, a sweeping ban of gender-affirming care such as hormones and puberty blockers for adolescents under 18. It also prohibits conversations around sexual orientation or gender identity in schools (a measure similar to the so-called “Don’t say gay” bill passed in Florida last year), will make school districts forbid trans students from using the bathroom tied to their gender identity and allow teachers to refuse to use students’ correct pronouns. Some are calling it an “omnibus anti-trans bill” and one of the worst in the nation.

This bill is just one of 434 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in State legislatures in 2023 according to the ACLU (the author of this article was a Communications intern for the ACLU affiliate in Kentucky from September of 2022 through November of 2022). SB 150 was vetoed by Democratic Governor Andy Beshear, but promptly overridden by the Republican-controlled General Assembly on March 29.

During the rally, supporters intermittently went to the center of the circle sharing stories, anger or just support to the crowd. Some of their words seared as they spoke from personal experience or passion for their community and classmates. A few students chose to lead the crowd in chants, similar to those during the walkout that Manual students staged a little under a month ago.

The rally was organized in part by Annika Gibson (11, MST) a well-spoken blonde who is trans and uses she/her pronouns. Although in the MST magnet, she’s less passionate about science and math and more into writing, attending Manual’s creative writing club every Friday. She loves writing both fiction and nonfiction, but has recently been more preoccupied with the latter, writing about trans issues and making the instagram account “protect_transky”.

She and her friends organized the rally in two weeks and although the rally was small, she felt she had to do something.

“The thought process was I can either sit here and watch as my rights are stripped away or do something and at least have a chance at putting a dent in the legislature and getting them to stop what they’re doing,” Gibson said.

The two rallies were ultimately a culmination of trans Manual students watching as anti-LGBT and anti-trans bills gained more traction, developing a real shot at passing. Although Emma Hicks (12, VA) a trans student that uses she/her pronouns, knew Louisville was not going to try to pass discriminatory ordinances; as other states began to introduce similar bills, Kentucky’s willingness to pass bans seemed obvious.

“I saw it almost as like an infection spreading,” Hicks said.

Most transgender teens are just like other teenagers, with goals, ambitions, friends, favorite subjects and hobbies. As we talked, Hicks worked on collage work using vintage “National Geographic” magazines, one of the many mediums she enjoys working with.

One is a reluctant cellist turned prodigious musician, Elijah Wolff (10, YPAS), who is trans and uses he/him pronouns, talked in the YPAS black box theater as his orchestra class rehearsed music in a class over.

“At my base I want to help people like that’s just kind of something that’s like, present and like everything that I do basically with my instrument, I give people this performance,” Wolff said, his brown hair quaffed up on his head and cut short on the sides, wearing all black to match the setting of our interview. He’s a sociable and friendly sophomore passionate in talking about these issues. It becomes clear why he was the organizer behind the walkout staged at Manual.

But the legislation in Frankfort has elicited less joy in the teenagers and instead intense anxiety, anger and devastation. Though they’re only teenagers, many tried to articulate their right to be themselves with clear concision.

“It’s Horrific that people would rather me not exist like people would rather not have me exist at all than to take the time to get to know me,” Wolff said.

Wolff specifically has been on testosterone (sometimes colloquially called “t” in the trans community) after being formally diagnosed with gender dysphoria, described as “psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity” by the American Psychiatric Association in 2020. It is a feeling he’s had his entire life.

“I remember seeing my dad without a shirt off, and I was like, hey, why can’t I do that? And it was like, you just can’t,” Wolff said.

After puberty, his dysphoria worsened and he went into therapy where he was diagnosed and started the process to obtain hormone therapy. Since going on testosterone, Wolff described a feeling the happiest he’s ever been but worried that it may be taken away.

“Yesterday was six months on testosterone and it was very almost emotional because it was like I was thinking like is this one going to be like one of the last times that I get to celebrate this?”

This process in particular isn’t easy to go through, requiring rigorous informed consent for adolescents according to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s (WPATH) standards of care. Sometimes finding a provider is half the battle.

Gibson also described a similar process as Wolff to obtain gender-affirming care, describing “All kinds of therapy and medical appointments, just to make sure my body could handle it.” Her journey to coming into her identity was “the classic trans origin story” and came out to her parents in 2020. She was able to obtain a prescription for hormones the day that House Bill 470 (a bill that would ban her gender-affirming care) was introduced, the bill that would eventually merge with SB 150. The anger she felt was palpable.

“I found out about it the next day here at school and punched a wall and that’s not hyperbole.” The reaction was strong because of the reality of what this healthcare does for transgender teenagers: “I don’t know how to describe it other than just sheer unrestrained joy that will then be taken away.”

The wait for hormones can often be excruciating, one student who only wished to be identified as Max (11, YPAS) said the process was long and still ongoing with several bumps in the road.

“It was almost a year before I was actually able to see a gender therapist and then she’s gone.” Max said. Healthcare professionals such as pediatricians often aren’t trained on how to address LGBT health needs, meaning many need to go to specialists that sometimes aren’t covered by insurers or have long wait times.

With this care banned in Kentucky, Max is worried what the wait will do to his friends who are younger. “They’re like 16 now and they have to wait two years, that doesn’t seem horrible, but to them that is an internal conflict for two more years of them trying, just not being in the right body.”

The effects extend past just doctors offices and into schools as well. With “don’t say gay” provisions, bathroom bans and preventing schools from recommending or requiring teachers from using pronouns if they’re in conflict with a student’s birth certificate; the school environment has come directly in the crosshairs of SB 150. For many LGBT students, school is often the first place they express their identity. “I see it as a chance for me to kind of explore myself in a little bit of a safer place than I would at home […] I feel excited to go to school,” Hicks said.

At school, Hicks hangs out with the art kids in the literary magazine “One Blue Wall”. She often wears loose sweaters with her wire frame glasses. She loves school and the community around her, but as graduation grows nearer, it’s clear that staying in Kentucky isn’t an option.“I just feel like I cannot be myself in Kentucky.” Instead she’s looking beyond the state for a career in graphic design.

Max expressed a similar sentiment “I do want to leave. I really do. But will I be able to financially? Probably not.” Moving far away doesn’t seem like an option, but with Tennessee, Missouri and Indiana all proposing similar legislation, choices are slim. “Illinois is the best I got.”

With SB 150 enshrined into law, a fear of what’s next blooms, but also a hope for recognition in a long battle; several Manual teachers have begun wearing cards that say “I’m here” displaying different pride flags on their lanyards and students in classes discuss the issue more since the walkout. They hope for soon people will realize that they’re just like them and repeal these laws, even if it takes 20 years.

“And if it’s 20 years?” Gibson tells me in an even tone, “People may realize that ‘hey, trans people are just random individuals who are trying to live out their lives.’”

Hicks has continued to work on her art throughout the school year, often analyzing her identity through her work. Her favorite being sculpture she made out of clay and welded metal reflected on a moment in 2020 which she characterized as a “crash”, literal and metaphorical, in her life of both realizing her gender and getting into a bicycle crash that severely injured her. The industrial bare bone of the foot being slowly recovered by new clay, on her terms.

“I turned it into a chance to rebuild myself and start anew. And so I see that leg piece as kind of looking at that, where I go from the bare bones of the metal to something that I can mold into my own.”