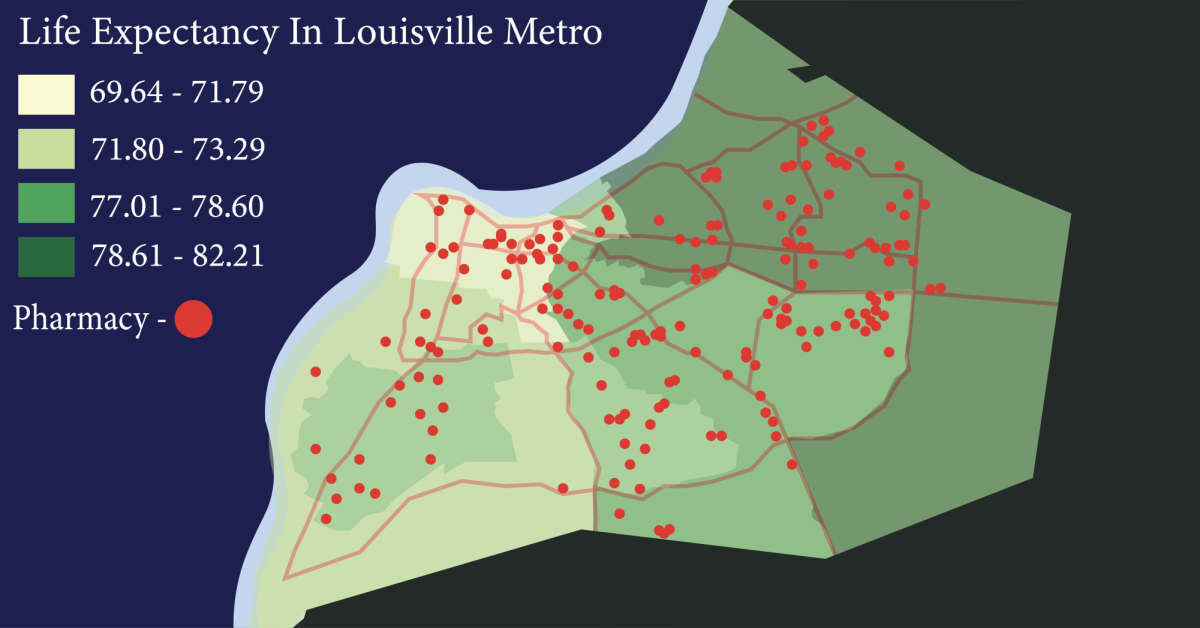

In some areas of the West End, contemporary poverty levels remain as high as 80%. Louisville’s history of segregation has left the area generally underdeveloped, and as national economic troubles force pharmacies to close, it is in the West End where the pharmacy desert weighs hardest on the population.

The impact of the pharmacy desert should be highlighted as a driver of low quality of life, working in tandem with existing poverty to worsen health inequity. Louisville citizens should exercise their civic duty to drive focus towards decreasing the West End pharmacy desert.

Pharmacy deserts can be defined as neighborhoods with low proximity to pharmacies. To understand how pharmacy access can specifically improve health equity in Louisville’s West End, it is important to assess the depth of health inequality in Louisville and the effects it has on the population. In the city, Black people die at a higher mortality rate than white people from six of the eight leading causes of death in Louisville, and have a higher overall death rate than the city’s white population. This race-correlated inequity can be attributed to health disparities in the West End, which has the highest percentage of Black people in the city. Giving focus to the West End, therefore, should be a natural course of action.

Pharmacies have been proven to lower mortality and improve health outcomes in nearby communities by lessening disease rates through vaccination and medicine distribution. However, many factors inhibit pharmacy presence in the West End, suppressing their ability to improve local health.

One of the most apparent obstacles to the average consumer is the rising cost of drugs, which is part of a general trend of nationwide inflation. From January 2022 to January 2023, drug prices increased by an average of 15.2%, or $590 per medication. In a 2018 survey of 3,500 Jefferson County residents, nearly a fifth of respondents reported that unaffordable prescriptions were their largest barrier to receiving healthcare.

Understanding why drug prices are rising is crucial to lowering them. One of the primary reasons for the increases is the will of pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs). PBMs are third-party administrators contracted by health plans and government entities to manage prescription drugs sold at pharmacies. These organizations control copays and make a profit by purchasing medicines from suppliers, then upcharging them before selling them to pharmacies. PBMs often give rebates back to successful pharmacies, but never to the end consumer. They are also highly unregulated– three PBMs control nearly 80% of the pharmacy benefits market– and their unfair practices lead to unfair drug prices.

The impact of these prices can be seen in pharmacies all around the local area. Anthony Westmoreland is the owner of Westmoreland Pharmacy and Compounding in New Albany, Indiana, and he claims that PBMs have forced his pharmacy into closure.

“PBMs provide contracts which have become very aggressive in cutting pharmacy’s reimbursement… All contracts are “take it or leave it”, meaning there is no negotiation. Even the chain drug stores are experiencing difficulty. For example, Kroger no longer accepts Express Scripts, which is a top three PBM. This means tens of thousands of people in the Louisville Metro area cannot go to Kroger to have their prescription filled [if their insurance contracts with Express Scripts],” said Westmoreland.

According to the Kentucky governor’s office, two PBMs made $123.5 million in profit in 2018 from the state Medicaid program by paying pharmacies a lower rate to fill prescriptions, while charging the state more for the same drugs.

Legislators have recognized the unregulated behavior of PBMs and have previously attempted to impose restrictions on them; Kentucky House Bill 457 and U.S. Senate Bill 127 both aim to outline regulations for PBMs and increase transparency in their dealings, but neither have passed. This shows that local voters and advocates must do more to support PBM regulation.

In addition to facing increased drug costs, West End residents who rely on chain pharmacies also find their local stores closing or reducing their hours after the pandemic. Walgreens closed four Louisville locations in late 2022, all of which were in the West End or downtown, and CVS has closed more than 1,100 locations nationwide since 2018.

According to health services researcher Jenny Guadamuz and associates, “…pharmacy closures [are] more common in Black and Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods.” In her research, Guadamuz found that because pharmacies in minority neighborhoods are statistically more likely to serve customers on Medicaid or Medicare, they are generally lower-profit locations and more expendable to a large chain.

To combat this, cities must invest in independent pharmacies instead, which can provide more tailored services for a particular community, can build closer relationships with their patients compared to large, inflexible pharmacy chains and are less likely than chain stores to close in minority communities.

The Louisville Metro government has the legal means to use tax-increment financing districts (TIF districts) to divert local taxes to give extra funds to certain industries in certain areas of the city. This would allow the government to incentivize the building of pharmacies particularly in the West End. Yet, the local government has not taken advantage of tax-increment financing so far, and the only existing TIF district covers only ten square miles and leaves out a majority of the West End. Louisvillians must make their voices heard in order to make pharmacy investment a priority for the Metro government.

In addition to increasing pharmacy presence, making Louisville more walkable will allow citizens to have better access to both existing pharmacies and new pharmacies that will be present in the future. There are many existing initiatives to make Louisville more walkable, including the Preston Corridor Plan and Reimagine 9th Street. These initiatives should continue and be expanded to include more of the West End. Walkability also has added benefits of decreasing local obesity rates and increasing local engagement in the community, which will only benefit the health and happiness of Louisvillians.

However, for disabled or elderly citizens, citizens who live in high-crime or dangerous areas or even citizens with no private transportation, visiting pharmacies in person may not be feasible, even if more are built or walkability is increased. Thus, expansions in telemedicine and mail-order pharmacies are necessary to allow those citizens to obtain the medicine they need.

According to telemedicine company CirrusMD, telemedicine is underutilized, accounting for approximately 21% of total healthcare provider visits, down from 69% in April of 2020. Petitioning our city and state government to improve broadband internet access would have multiple benefits, including increasing access to mail-order pharmacy services and online meetings with physicians.

“I like mail-order pharmacies better than the alternative,” said West End resident Maryetta Montgomery. “For one, when [brick-and-mortar] pharmacies reduce their hours, it’s harder to get to them when I need to, especially now that I’m not driving anymore after my stroke. Some medicines are cheaper at the physical pharmacy though, and I have to get all my immunizations there too.”

Physical pharmacies still have an important role to play in immunizations and in dispersing time-sensitive medications such as antibiotics, meaning that both areas deserve investment from the government and focus from entrepreneurs.

However, it is important to concede that simply increasing pharmacy access will not completely eliminate healthcare inequality. Other societal and systemic problems exist that pharmacies cannot solve; for example, people of color are more likely to experience mistrust of the medical system or forgo vital operations due to knowledge of past and present discrimination in healthcare, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.

Yet, because pharmacies have such wide capacities, they hold a unique ability to improve health outcomes in underserved communities, making investment in pharmacies a valuable step in a larger health equity plan. In addition, the interconnected nature of the roots of general inequity means that multiple facets of the issue can be solved with the same initiative. For example, expanding the number of grocery chain stores with built-in pharmacies in disadvantaged areas can be expected to alleviate both food deserts and pharmacy deserts, just as increasing walkability will both increase public health and pharmacy access.

The CDC defines health equity as “…when everyone has the opportunity to be as healthy as possible.” Although increasing pharmacy access will not completely solve the health crisis, it will prove to be a cornerstone of a multi-sectoral approach that can bring lasting health equity to the West End. While the most important changes can only be made at the government level, Louisvillians cannot discount using civic engagement to make the pharmacy desert an important policy issue. Advocating for initiatives that would drive funding toward independent, chain and mail-order pharmacies in the West End and voting for representatives who stand for eliminating health inequity are the most important actions we can take as citizens.

Every Louisville resident deserves access to the health services they need. No one voter or policymaker can ensure this alone, however. Only by working together can the city ensure that Louisville is a healthy, equitable community.