OPINION: My education in Critical Race Theory

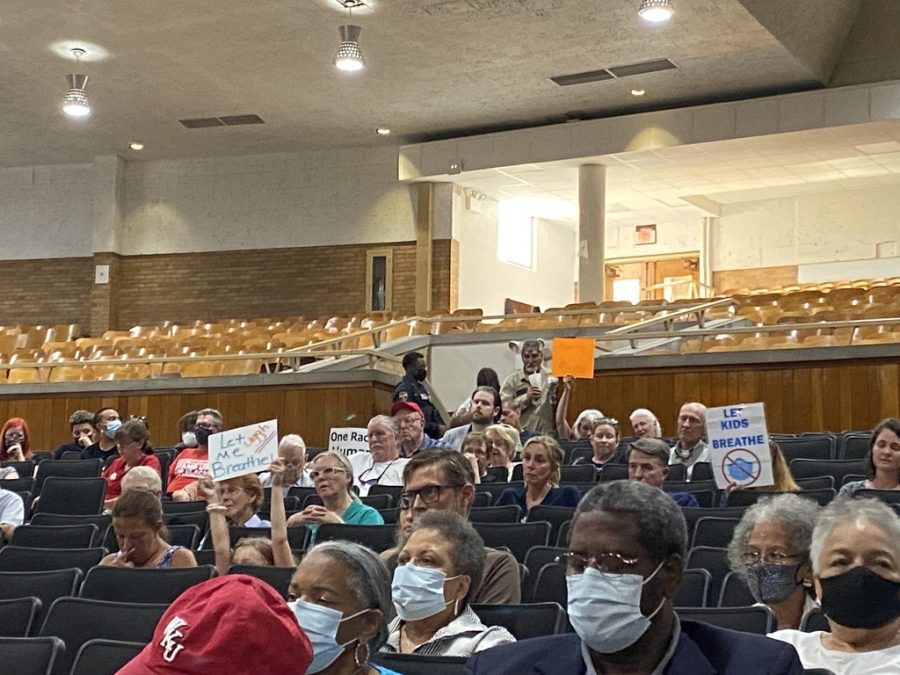

Many citizens showed their support against masking in schools and Critical Race Theory at the Kentucky Board of Education meeting. Photo by Brennan Eberwine.

August 20, 2021

Summer is typically the quietest time in terms of news in education; but, this hasn’t been a typical year. All anyone could talk about was Critical Race Theory (CRT) and its perceived equivalents.

Bills restricting discussions on race and the effects of racism moved through and became law in Tennessee, South Carolina, Texas and Oklahoma. Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project were explicitly banned from being taught in Florida. Meanwhile, two bills attempting to ban CRT have been prefiled in the Kentucky legislature.

What even is Critical Race Theory? I personally hadn’t heard of it in more than passing context and never devoted much energy to really think about it. However, it became a pretty hot topic for parents, teachers and students to discuss as the summer and legislature activity wore on. So I dove in and tried to understand one of the most divisive issues of the summer.

The concept of Critical Race Theory has existed since the 70s. It began its life as Critical Legal Studies and was originally explored in law school, used as a lens to look at multiple facets of American life. Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, one of the first to apply the theory in education, explained it in an NPR interview as, “…a series of theoretical propositions that suggest that race and racism are normal, not aberrant, in American life.”

Essentially, the theory posits that many of America’s institutions uphold and reinforce inequality towards Black Americans. Dr. Ladson-Billings gave examples of how it occurs, such as unequal access to medical care or curricular access in education. Individual laws can also uphold racism, such as the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. This Act, better known as the 1994 crime bill, made the punishment for possession of crack (a drug typically used by impoverished Black Americans) more severe than the punishment for possession of cocaine (a drug typically used by wealthier White Americans). Both drugs are equally detrimental, yet Black Americans face harsher consequences.

I attended and live tweeted the Kentucky General Assemblies Joint Education Meeting on July 6th, where the legislature discussed CRT in educational settings and bill BR 69. There were a lot of anti-CRT positions and claims that CRT was being taught to younger students.

“It’s typically a graduate level academic theory or concept taught in law school,” Dr. Jason Glass, Kentucky Commissioner of Education, stated, “That being said, some parts of Critical Race Theory are taught in high school electives that considers the historical, political and sociological aspects of racism and events.”.

Even though I’ve had CRT explained to me multiple times by multiple people, I still have trouble completely grasping the full concept of what exactly it is. My own inability to grasp the concept is why it baffled me that all of these adults thought CRT was something that could even be effectively taught in elementary school.

Following Dr. Jason Glass’s explanation of CRT was Rep. Matt Lockett’s (R)-39 own thoughts on the matter. He cited Critical Race Theory as “identity-based Marxism ” and asserted that it was Marxist, racist, rooted in communism, a ploy by the left-leaning media and that it was trying to dismantle America. The prevalent use of buzzwords and lack of legitimate, relevant evidence for his argument further proved to me that his speech was more of an attempt to incite fear…

I found it problematic that Rep. Lockett essentially ignored Dr. Glass’s definition because it didn’t fit his own anti-CRT narrative. He attacked an idea of CRT that didn’t really exist instead of arguing against the actual theory. After the meeting, Rep. Lisa Willner (D) – 35 commented that, “there were just a lot of buzzwords that people of a certain political persuasion get really worked up about, there was no substance and the presentation also did not address the bill.”

Many Representatives and Senators at the meeting pointed out that BR 69 was vague and that it’s difficult to understand what the bill is trying to accomplish. I couldn’t figure out how this bill bans CRT, even after reading it multiple times. The entire conversion seemed like less of an argument against CRT and more of a strawman situation, yet another issue to drum up people’s emotions and further political agendas.

It’s also worth pointing out that this Kentucky bill uses almost the exact same language as bills in more than half of other state legislative bodies; of which can be traced back to the Ethics & Public Policy Center as well as Christopher Russo, a filmmaker and independent journalist.

The day after I attended the Kentucky General Assemblies Joint Education Meeting, an organization called No Left Turn in Education, which hopes to ban “…aggressive, radical totalitarian ideology. From The 1619 Project, to Critical Race Theory, to Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE),” from schools, hosted a “community forum” called Education not Indoctrination.

At this in-person community forum, Fayette County teacher Delvin Azofeifa and former teacher Irina Baptiste, whose teaching license was revoked in 2008, presented what they referred to as the dangers of CRT. Mr. Azofeifa repeatedly claimed that “Critical Race Theory adjacent dogma,” a term he never actually defined, had infiltrated schools and that CRT only assumes America has had slavery and that CRT is simply a product of Marxism. Ms. Baptiste claimed CRT was a part of, “the latest communist effort to conquer the world,” among other things. Despite making far-fetched and often outlandish claims, both speakers garnered rapturous applause. To be completely honest, this “community forum” leaned more towards being called a rally than anything else.

I spoke to a woman at the No Left Turn Event off the record. She talked about how she was worried about what her grandchildren were being taught in school. Although she could not specifically define what CRT is, she did claim that it was Neo-Marxist. As I talked to her, it was clear to me that she had never actually read anything on CRT, but instead was just parroting talking points repeated by multiple right-wing politicians or from events such as this one.

I slowly learned that the definition of Critical Race Theory stemming from the anti-CRT movement is not an accurate depiction of what it is. They are fighting against their own false projection, pulling from an amalgamation of topics that have recently become a part of the flash points in public education politics.

I’ve heard trauma-informed teaching, the JCPS Racial Equity Policy and inclusion of more diverse historical figures and stories all used as examples of what CRT is from anti-CRT activists. Many anti-CRT activists also disparage recent popular literature on race and racism, such as Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist and Robin DeAngelo’s White Fragility. Neither of these authors are CRT scholars nor do their books contain any material on such, so the anti-CRT critiques of these books are not grounded in any substantive arguments.

Ultimately, I believe that the anger surrounding CRT is a red herring to limit academic freedom and prevent honest conversations around race. Teaching divisive issues in schools has always been a hot topic and hot button issues have always existed within education. These can range anywhere from accurate depictions of slavery to assigning texts such as Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi or Beloved by Toni Morrison. There are people rallying against these teachings and they’ve found a new outlet in hopping on the anti-CRT wagon.

I have almost finished my academic tenure in the public school system and the class conversations that have stuck with me the most have been the hard ones. Times I wasn’t just asked to read the passage, but when I was pushed to examine and defend my belief system and think about the real world and the difficult and uncomfortable situations. To sell students so short, to say that nothing controversial or uncomfortable can be in schools does not improve schooling, it creates an awkward bubble of misinformation or blatant ignorance.

The United States has been struggling with its identity from the very beginning. Are we the great nation who fights fascism or the one who sent thousands of Native Americans to live on reservations? Are we the nation who uplifts democracy around the world or the one who tears it down when elections don’t favor our interests? The United States, like all nations, is neither the bastion of good or the epitome of evil. Even if it is one or the other, it seems to me that the line of good and evil is blurred.

What we owe to the students across this country is an honest history, one of struggles and triumphs, of good and bad and of depictions of real people and not just caricatures. That means confronting our past and having hard conversations, making students and maybe even teachers uncomfortable. It’s worth it to uplift the next generation of students and give them the tools so that they may envision a United States that can truly claim liberty and justice for all.

Kristin Gaydos • Aug 23, 2021 at 9:25 am

I 100% agree! Amazing article!!