Hurricane Ida is reflective of our changing climate situation

September 18, 2021

Category four Hurricane Ida made landfall on Sunday, August 29 in Port Fourchon, Louisiana. It’s near 150 mph winds tested the limits of a category five, the most intense category of hurricane, classified by 157 mph winds. It’s intensity was also reflected in it being the seventh-costliest natural disaster the United States has seen since 2000.

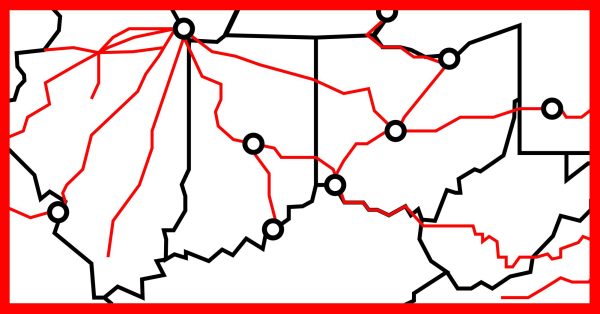

The tropical storm was first noticed as a depression with, “the potential for tropical cyclone development.” From there it strengthened to a category one hurricane on August 26 and began heading towards the Cayman Islands. Hurricane Ida intensified to a category two after passing over Cuba and then grew even more powerful when it swirled into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Hurricane Ida took its time to slow down after making landfall on the Louisiana coast, rather than fading quickly as many storms do once they hit land. Ida eventually recessed from a hurricane back to a tropical depression and the first few days of September saw what was left of the storm making its way to the northeastern U.S.

Nearly one million residents in New Orleans were left without power and at least one person was reported dead from Ida. That number is subject to increase as damage is still being assessed. Government organizations and nonprofits, such as the American Red Cross, immediately got to work trying to provide relief to Louisianians.

“We’re making every effort to learn more and rectify,” said Entergy New Orleans on Twitter.

Ida didn’t do nearly as much damage to the levees or overall in comparison to Hurricane Katrina, which occurred exactly 16 years before. However, it’s been dubbed the second most devastating to hit Louisiana and is part of an even more important category.

Recent years have seen the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center (CPC) update its definition of the average hurricane season. Now, “the “above average” season prediction will be higher than previous predictions for an above-average season based on the changes of what is considered average.”

The ramifications from Hurricane Ida extended beyond states like Louisiana and went on to touch further up the country. For example, New York was left heavily impacted from Ida’s aftereffects. Streets and highways were flooded. People drowned in their own homes. The subway was inundated and had to be shut down temporarily.

”The climate crisis isn’t coming, it is already here,” Rosecrans Baldwin wrote.

According to Yale Climate Connections, the climate crisis is responsible for these stronger and more frequent hurricanes. The warmer the water, the more heat energy formed and the higher the chance for a tropical cyclone to form. So warmer water equals a higher probability for hurricanes. Results of a study in 2013 discovered an increase in category four and category five hurricanes, which are the two strongest categories. “We believe based on our modeling studies that hurricanes are likely to become slightly more intense with global warming,” said Tom Knutson, a climate scientist.

The brown ocean effect will likely become more common with the increase of global warming and helps explain the slow decline of a hurricane due to certain natural circumstances. Warm, moist ground provides a similar environment to the ocean and maintains a hurricanes’ strength for an extended period of time, rather than the storm weakening rapidly.

Ida isn’t the first, as we can see from Katrina, nor will it be the last hurricane to be impacted by global warming. As water temperatures continue to rise with the warming of the Earth’s atmosphere, more areas of the ocean become zones for the formation of hurricanes. Hurricanes will become more frequent and rare scientific occurrences like the brown ocean effect will become more common, causing storms to become more intense. In the future, hurricanes and climate change will continue to impact all of us and not for the better.

Kathy Barber • Sep 19, 2021 at 9:06 am

Another fine, well written article by Kaelin! Enjoy reading your articles.